Put the Christ back in Christology

Calling Jesus “the Christ” is declaring him the ruler chosen by God to restore heaven’s reign to the earth.

Christology is the study of Christ. Well, that’s what it would be if it focused on the Christ bit.

These days, Christology is a branch of theology, the study of God (theos means God). Systematic theology starts with God, so Christology usually fits in as the study of the second person of the trinity. It discusses how Jesus could have two natures without his divinity messing with his humanity and vice versa. It rehearses how early Christians struggled with wrong ways to talk about God (heresies) and eventually found the right language (the creeds and Symbol of Chalcedon).

That’s all important, and I’m truly grateful for these great summaries of what we believe. But along the way, the emphasis shifted. Christology lost its focus on the Christ.

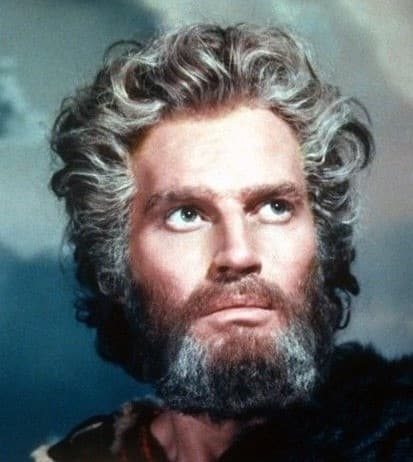

That word has a specific meaning in the narrative of the kingdom of God. The Christos is the anointed person.

When God founded a nation under his governance, priests were anointed to mediate the relationship between the heavenly sovereign and his people. When they needed human leaders, judges and kings were anointed to lead on God’s behalf. When kings strayed from representing their heavenly king, he anointed prophets to call them back. When the kingdom fell apart, prophets like Isaiah, Ezekiel, and Zechariah promised the restoration of his anointed king and priest.

In Jesus’ time, Israel had priests again, but they yearned for the day when God would send them his anointed king. When we call Jesus the Christ, we’re claiming that he was the ruler chosen by God to restore heaven’s reign to the earth.

Christology is about his kingship.

More than 500 times, the New Testament calls Jesus Christos. The watershed moment of Mark’s Gospel is when Peter declares, “You are the Christ” (Mark 8:29). Luke strengthens that declaration to ensure we understand it meant the ruler appointed by God: “You are the Christ of God” (Luke 9:20). Matthew adds a parallel phrase so we cannot miss the allusion to Psalm 2 where the Davidic king is proclaimed as God’s anointed son: “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God” (Matthew 16:16). John doesn’t report this event, yet he uses Christos to describe Jesus more than the other Gospels, starting by identifying Christos with the Hebrew Messiah, the long-awaited Davidic king (John 1:41).

Almost every chapter of Acts uses Christos as the crucial apostolic declaration of Jesus. For example, Peter’s message was that, “God has made him both Lord (master/ruler) and Christ (anointed king)” (Acts 2:36).

Paul used Christos 66 times in Romans, and it was not a mindless title! His gospel declared Jesus as the anointed king, physically descended from David, the representative on earth of heaven’s power. Paul finds his own identity as a servant of this king (Christ Jesus): he is commissioned in an ambassadorial role to proclaim the in-breaking of God’s reign (“the good news of God”) so that King Jesus receives the obedience of the nations. All of that is in the first six verses of Romans, and the theme continues to the very end (16:25-27).

The New Testament letters call Jesus Christos 3 or 4 times every chapter on average. No wonder the study of Jesus is called Christology!

Can we recover a Christology of Jesus as God’s chosen ruler over us, implementing heaven’s reign on earth? We lose the main message if we don’t.

What others are saying

Martin Hengel, Studies in Early Christology (London; New York: T&T Clark, 2004), 2:

Within an amazingly brief period Christians changed the title Christos into a name and thereby usurped it for the exclusive use of their Lord, Jesus of Nazareth.

N. T. Wright, Paul and the Faithfulness of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2013), 518:

It has of course been fashionable for most of the last century at least to treat Christos in Paul as merely a proper name, with only one or two occurrences retaining any titular, ‘messianic’ meaning. But it is time to put this right, and to insist that in passage after passage Paul’s long, essentially Jewish, narratives, in which this Christos figure plays the decisive part, cry out to be seen as ‘messianic’, albeit of course redefined by the events themselves.

Craig S. Keener, The Gospel of Matthew: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2009), 61, 67-68, 70:

More important than his portrayals of Jesus as a teacher and prophet, Matthew hails Jesus as the true king of Israel (2:2; 21:5–9; 25:34; 27:11, 29, 42; of God in 22:2), that is, the Messiah (Christ; 16:16–20). Jesus’ teachings have such special authority for Matthew’s Jewish-Christian audience precisely because he is God’s appointed king. …

Yet for all this “high” Christology, it is hardly Matthew’s emphasis (cf. Pregeant 1996); Matthew devotes far more space to Jesus as authoritative teacher, Messiah (rightful King of Israel), the fulfillment of ancient Israel’s history and prophecies, and so forth (on Matthew’s Christology, see especially Kingsbury 1975). …

Jesus’ teaching is supremely authoritative precisely because he is the rightful ruler of Israel, God’s Son the Messiah (16:16–17).

Michael F. Bird, Evangelical Theology: A Biblical and Systematic Introduction (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2013), 346:

Having established that Christology is the study of the person and work of Christ, we still have to inquire as to the best way to go about that task. Method in Christology is a notoriously disputed affair. How do you teach someone about Jesus? Do you start with the person of Christ or with the work of Christ? Do you start with the Gospels or the epistles? If Gospels, would you start with Mark or with John? Should we begin with a full-blown Nicene Christology or work our way up from the historical Jesus? Do we study Jesus based on titles given to him, like “Son of God” and “Son of Man,” or should we prioritize things Jesus did and accomplished, like his miracles and teaching? These are the issues.

The debate about the method for Christology is often posed in terms of “Christology from Below” versus “Christology from Above.”

[previous: Jesus’ liberating kingship]

[next: Should we keep the Sabbath on Saturday or Sunday?]

Seeking to understand Jesus in the terms he chose to describe himself: son of man (his identity), and kingdom of God (his mission). Riverview College Dean

View all posts by Allen Browne