Declaring Jesus king (Matthew 16:13-16)

“Do you believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God?” It’s the question I often ask when baptizing believers. Our faith is in a person, and Peter nailed it with his declaration. So, what did Peter mean by this great confession?

There’s a temptation to invest Peter’s words with later theological meaning and miss what he said. His phrases have snowballed with significant theological freight:

- Christology is the study of the person and work of Christ. His person embodied two natures (fully God and fully human), so his work reconciled God and humans (atonement).

- Son of God is a term we associate with trinitarian theology: the relationship between Father and Son who, with the Spirit, exist eternally as one God (trinity).

All of that is true and important, but this developed theology was not in Peter’s mind. Rather than treat his words anachronistically, let’s hear them in their context.

Christ / Messiah

For many of us, Christ is just another name for Jesus. We read, “Christ died for us,” and what we hear is “Jesus died for me” (rather than a king dying for his people). That’s not how Peter was using the word. He wasn’t saying, “We think your name is Christ; you know, like, you’re Jesus.”

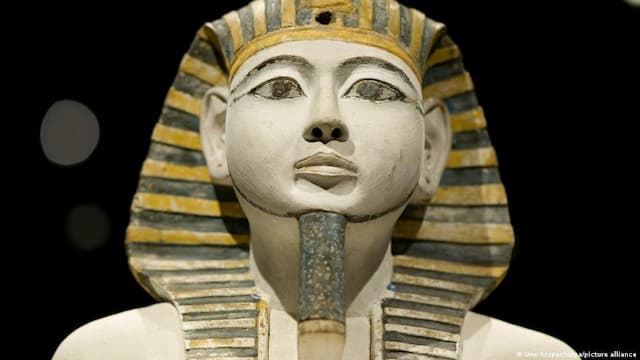

Christ was a title. The Greek word christos was transliterated into English as “Christ,” just as the Hebrew word ma·siah was transliterated as “messiah.” Both words mean “anointed.” There were many christs / messiahs — people anointed in recognition that God had chosen them to represent him. Kings and priests were anointed, and occasionally a prophet.

In Jesus’ time, there were many anointed priests. Following the 70 years in exile, the temple had been rebuilt and priests anointed. But the kingship had not been restored. God’s people lacked an anointed king. The prophets declared God’s reign would be restored (e.g. Isaiah 40), but there was no anointed king representing his reign on earth. Matthew’s opening claim is that Jesus is the anointed king they’ve been waiting for, “the Christ, son of David” (1:1).

Psalm 2:2 describes the earth as governed by “the Lord and his anointed.” This phrase (YHWH and his ma·siah) is explained in the following verses: “the one enthroned in heaven” (v.4) and “my king installed on Zion” (v.6). On the day of his coronation, the chosen son of David was declared to be “the son” who represented the heavenly Father’s rule on earth (v.7). Just as Israel was “my son” (Exodus 4:22-23), the authority God gave to the Davidic king made him “the son” of the heavenly ruler (2 Samuel 7:14).

In Psalm 2, then, God’s “anointed” (ma·siah / christos) and God’s “son” are two expressions for the same thing. When Peter called Jesus the Christ and the Son of God, was he making two separate statements about Jesus’ identity? Or was he offering two expressions of the same truth, phrases in apposition as in Psalm 2?

The Gospel writers did not believe Peter made two Christological statements. If Peter wanted to say, “and we think you’re the second person of the trinity also” then Mark either missed the point or thought this wasn’t important enough to record:

Mark 8:29b Peter answered, “You are the Messiah.”

Luke didn’t think the second person of the trinity bit was worth saying either:

Luke 9:20b Peter answered, “God’s Messiah.”

Rather than argue that Mark and Luke both missed the point, it would be better to recognize that Peter was making a single point, that Matthew’s two phrases both express the same truth. In Matthew, the Christ means the son who represents the heavenly sovereign’s reign on earth — exactly as these phrases are used in Psalm 2.

Why this matters

Peter’s definitive confession is that Jesus is king. They’ve been waiting for the anointed ruler to restore God’s reign over his people, the prince who restores on earth the government of their Father in heaven. The gospel is the good news of his kingship, so the response to the gospel is naming Jesus as king, giving him allegiance.

In Peter’s mind, they can now march off to Jerusalem to have Jesus crowned, to have everyone recognize the king anointed by God. Jesus affirms that he will establish his government and the gates of death itself cannot stop him (16:17-18), but the process by which he becomes king will be messier than Peter imagines (16:21-28).

Don’t let that detract from Peter’s great confession. He recognized the Christ, God’s anointed ruler, the Son who restores the reign of the living God, with earth as the community living under his reign.

Peter’s confession was Jesus’ kingship.

Recovering this good news

How did we lose this gospel focus? As Jesus warned (16:21), Israel’s leaders did not accept his messiahship (his kingship). It didn’t help when the temple was destroyed in AD 70, just as the king had told them. Initially, Christians were a branch of Judaism, but ultimately Christianity became a separate faith in what the late James Dunn called The Partings of the Ways (London: SCM Press, 2006).

This tension between Christianity and Judaism naturally caused the church fathers to emphasize the universality of Jesus and deemphasize his Jewishness. Some of them argued passionately against the Jews. By the Middle Ages, the treatment of Jews by Christians was often shameful. Some of Martin Luther’s later polemic against Jews was frightful, fodder for the Nazis.

For 2000 years, we have deemphasized Jesus’ kingship. It’s easier to develop a theology about the Son than to live as the community of the Son. It’s easier to package the gospel as a personal experience than to live together as the reconciled community of the king.

To recognize Jesus as “the Christ, the Son of the living God” is not a personal faith; it’s a communal one. In saying he is king, we are his kingdom. In declaring him as the Son who brings the living God’s reign to earth, we are the human family he’s restoring. The image of the living God is the community reconciled in him.

The gospel calls people to recognize his kingship, to embody life as his kingdom.

Whatever else we want to say about Jesus, the gospel is his kingship. God has anointed no other leader, no other name through whom the world can be saved.

Open Matthew 16:13-16.

What others are saying

Tom Wright, Matthew for Everyone, Part 2: Chapters 16-28 (London: SPCK, 2004), 7:

It’s important to be clear that at this stage the phrase ‘son of God’ did not mean ‘the second person of the Trinity’. There was no thought yet that the coming king would himself be divine—though some of the things Jesus was doing and saying must already have made the disciples very puzzled, with a perplexity that would only be resolved when, after his resurrection, they came to believe that he had all along been even more intimately associated with Israel’s one God than they had ever imagined. No: the phrase ‘son of God’ was a biblical phrase, indicating that the king stood in a particular relation to God, adopted to be his special representative (see, for instance, 2 Samuel 7:14; Psalm 2:7).

Seeking to understand Jesus in the terms he chose to describe himself: son of man (his identity), and kingdom of God (his mission). Riverview College Dean

View all posts by Allen Browne