Governing with God (Genesis 41)

From prison to palace in a single day! Are you encouraged by Joseph’s story? It’s more than personal encouragement. It’s God doing something enormous, global even. What does Joseph’s story teach us about the kingdom of God?

God gave the king of Egypt a dream (Genesis 41:1). Is religion meant to influence politics? Aren’t church and state too explosive to mix? I guess God’s not very good at staying out of the political arena.

So how does the kingdom of God relate to the kingdoms of the world? The heavenly sovereign has wisdom for earthly rulers. He’s the king above all kings. But how God does this is crucial:

- We misrepresent God when we withdraw from politics, as if God has no interest in the secular domain.

- We misrepresent God when we engage with the fights and factions of earthly politics, to force our will on the secular world.

Is there a third way? Joseph brought God’s wisdom to the secular world. In a land far from family and faith, with a meteoric rise from prisoner to prince, Joseph represented God well in Egyptian politics. Can we learn from him?

It all belongs to God

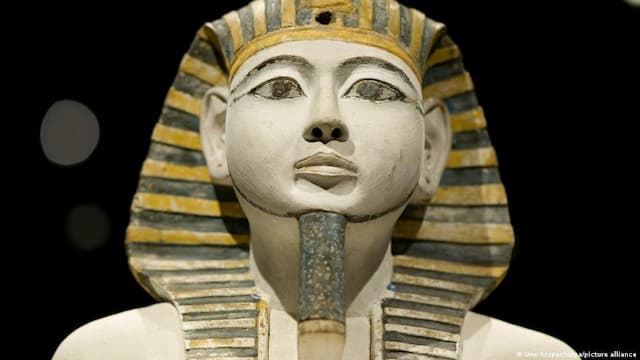

Like Jacob, Isaac, and Abraham before him, Joseph believed the whole world was God’s domain. His family was called to be a blessing to the nations (Genesis 12:2-3; 26:4; 35:11). So Joseph finds it perfectly natural that God would guide Pharoah in how to take care of the Egyptians through good times and bad. When the king has a dream (41:1), Joseph tells him, God has revealed to Pharaoh what he is about to do (41:25, 28).

The trouble is that Pharoah doesn’t know what to make of God’s guidance. With all his soothsayers and advisors, the king of Egypt has no one who understands God’s wisdom (41:8).

In hindsight, it’s so basic. God wanted the Egyptian government to use the good times to ensure they were ready to take care of the people in the bad times (41:25-36). As every farming community knows, these cycles come and go. But a seven-year drought is particularly difficult to survive, so God had alerted them so they had time to prepare.

Curious how God doesn’t prevent these things; he calls us to work with him in managing their impact. A government’s basic responsibility is providing for the needs of its people. This is what the prophets kept reminding the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, but it’s not just a Judeo-Christian ethic. People know this in their bones.

Often this isn’t the focus of our governments. I live in a state rich with resources. We had a mining boom in the early 2000s. But instead of paying off state debt to put us in good shape for the lean times, our government spent like there was no tomorrow, increasing state debt from $2 billion to $30 billion. Our rulers seemed more concerned with how to get re-elected than how to care for the long-term good of their people. I guess we still haven’t learned what God was telling Pharoah nearly 4000 years ago.

Joseph explained not only the dream but how to respond:

Genesis 41:33–35 (NIV)

33 Let Pharaoh look for a discerning and wise man and put him in charge of the land of Egypt. 34 Let Pharaoh appoint commissioners over the land to take a fifth of the harvest of Egypt during the seven years of abundance. 35 They should collect all the food of these good years that are coming and store up the grain under the authority of Pharaoh, to be kept in the cities for food.

Pharaoh gets it. A looming famine gives him a reason to increase taxation. While that’s never popular, it’s worth the gamble if it makes him the saviour of his people in the long term.

And appointing someone else to oversee this business is brilliant: if the famine never comes, he’ll have someone else to blame … as well as untold wealth. Pharaoh can’t lose: the guy who gave him this strategy can be the fall guy if it all goes pear-shaped.

So, that’s how one of Jacob’s sons became advisor to the most powerful ruler of the known world. In a single day, Joseph rose from prison, receiving all authority over the whole land, a signet ring to enact any legislation, a chariot backed by the Egyptian army, and enduring acclamation to ensure everyone recognized the ruler appointed by the king (41:42-43).

What changes?

Under Joseph’s leadership, there’s a shift in power. Everyone matters. Everyone is cared for. That was the message Pharaoh received from heaven. That’s the policy Joseph implements.

When Potiphar put Joseph in charge of his household, the Lord blessed the household of the Egyptian because of Joseph (39:5). Now Pharaoh has put Joseph in charge of Egypt, and the whole country is blessed because it’s following the wisdom of the God who’s with Joseph.

Joseph doesn’t start protest marches against the injustice of Egypt. He’s experienced it personally, both himself and others in Pharaoh’s prison. But instead of railing against the injustice of the empire, Joseph implements God’s care for everyone — the heart of the kingdom of God.

Is there a keyword in the closing verses of the chapter, something that points us to the extent of God’s caring provision for the world, implemented through Joseph?

Genesis 41:54–57 (ESV)

54 There was famine in all lands, but in all the land of Egypt there was bread. 55 When all the land of Egypt was famished, the people cried to Pharaoh for bread. Pharaoh said to all the Egyptians, “Go to Joseph. What he says to you, do.”

56 So when the famine had spread over all the land, Joseph opened all the storehouses and sold to the Egyptians, for the famine was severe in the land of Egypt. 57 Moreover, all the earth came to Egypt to Joseph to buy grain, because the famine was severe over all the earth.

All sorted?

How good is this? In Joseph, the blessing of God’s reign is being fulfilled in Egypt and spreading to the nations, saving many people (45:5; 50:20).

Is this what the kingdom of God looks like? Yes, and no:

- Yes: the heavenly sovereign is always reigning, caring for his people through those who recognize him, people like Joseph.

- No: the rulers of this world still refuse to submit to God’s authority, using the power God gave them for their own advantage.

The dream God gave Pharoah called him to care for everybody. Instead, Pharaoh uses the very wisdom God gave him to bring everything and everyone into slavery to himself (47:25). A later Pharaoh enslaves Joseph’s family too (Exodus 1:8-10). Jacob’s descendants must be freed from Pharaoh to be a kingdom of God.

And that kingdom falls too. Daniel and his friends end up working for the Babylonian king who destroyed Jerusalem. Their experience is so similar to Joseph’s as they try to show the rulers that it is God who reigns (Daniel 2:47; 3:28; 4:34; 5:22-28; 6:25-26). As history unfolds, it’s clear that the self-aggrandizing warrior-kings are beasts who will never recognize God’s reign. Only divine intervention can give the kingdom to someone human-like (Daniel 7). In generation after generation, they persist in denigrating God’s authority (Daniel 8–11), so only resurrection will overturn their deadly power (Daniel 12).

That’s why so many of God’s people suffered a trajectory like Joseph’s, going into exile to other powers. That’s why Jesus was betrayed by his own people, sold out to the nations who put the king of the Jews to death. And that’s why the son of man was raised up in a single day from the prison of death to global authority given by his Father over everyone and everything.

“Go to Joseph. Do whatever he tells you,” Pharoah said when they’d run out of food (41:55). “Do whatever he tells you,” Mary said when they’d run out of wine (John 2:5). “This is my Son … Listen to him,” the Father said as they glimpsed his glory (Matthew 17:5). “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Therefore go and disciple all nations,” the resurrected Christ told his followers, “… until the era is complete” (Matthew 28:18-20).

That’s why we can’t disconnect from the politics of this world if we’re serving Christ. It’s also why we can’t trust the rulers of this world, why we trust Christ. He’s the only ruler who is not self-serving, serving his people instead, trusted with divine authority to reign for everyone (Philippians 2:5-11).

Conclusion

God has not called us to disconnect from the governments of this world, as if religion and politics are separate domains.

God has not called us to critique the governments of this world, as if condemning them could restore what is right.

God has called us to recognize his sovereign authority over all nations. Every government, every leader is under his authority, and they will hear something of what God is saying. We can help them where they’re hearing God. But we can’t trust or expect them to save the world.

God has called us to embody Christ’s living leadership in his world, echoing God’s call to recognize his Christ as Lord of all.

This is how the kingdom of God works in the present evil age. We look forward to the day when our true leader does what no leader has done before: handing all regal authority back where it belongs (1 Corinthians 15:24).

In the meantime, we’ll work with Pharoah in whatever God is showing him, while our faith and hope are firmly planted in the only leader worthy of the name.

What others are saying

Dallas Willard, Living in Christ’s Presence: Final Words on Heaven and the Kingdom of God (Westmont, IL: IVP, 2013):

Jesus did three things in his own ministry: proclaim the availability of the kingdom of God to everyone, regardless of their standing in life; teach what it was like; and manifest its presence in events that could not be explained in a natural way. He is the master of that, and he invites us to step into that and to watch it happen where we are. It may be in a large church. It may be in a small church. It may be in an office. It may be in the responsibilities of a politically elected official.

Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 16–50, WBC (Dallas: Word, 1994), 400:

Joseph’s experience of release from slavery foreshadows that of his descendants, who later were released from Egyptian bondage. Yet again Christians have seen in Joseph a type of Christ, the greatest prophet and the greatest king. He too, like Joseph, experienced humiliation before exaltation. As all were commanded to bow before Joseph (v 43), so “at the name of Jesus every knee shall bow” (Phil 2:10).

Walter Brueggemann, Genesis, Interpretation (Atlanta, GA: John Knox Press, 1982), 328:

This new sovereignty is evidenced in its effectiveness by the multiple use of all: … all the land of Egypt (v.46); … all the food (v. 48); … all my hardship, … all my father’s house (v. 51); … all the lands, … all the land of Egypt (v. 54); … all the land of Egypt, … all the Egyptians (v. 55); … all the land, … (v. 56); … all the earth, … all the earth (v. 57). The repeated emphasis on “all” is not accidental. We may linger for a moment with its repeated use. A helpful comparison may be made with Psalm 145, a stylized doxology of God’s gracious protection and sustenance of all of creation.

Related posts

- God’s kingdom and politics

- Christ and the rulers of this world

- Don’t expect our politicians to be gods

- What kind of society do Aussies want?

- What is our role in his kingdom? and Alternative views of our role in his kingdom

Seeking to understand Jesus in the terms he chose to describe himself: son of man (his identity), and kingdom of God (his mission). Riverview Church, Perth, Western Australia

View all posts by Allen Browne