10 African-Americans You Should Never Forget

February is a month not lacking for its traditions and special days. From Groundhog Day to Valentines Day, it is easy to lose yourself in these mid-winter celebrations and observances.

Perhaps the most significant celebration has nothing to do with Puxatawny Phil or honoring the ones we love. February also marks Black History Month, a month-long observance in North America that remembers the indelible sacrifices made by so many African-Americans to make the world around them a more equitable, fair, and impartial place to live.

Certainly no month should ever pass that we don’t take a step back and honor the remarkable and significant contributions of African-Americans in American history.

So many people and accomplishments come to mind … Phyllis Wheatley, Robert Sengstecke Abbott, and W.E.B. Dubois from years gone by, in the arts, Toni Morrison, Alex Haley, and Maya Angelou, to sports, Jackie Robinson, Muhammed Ali, and Bill Russell, and more recently, John Lewis, Colin Powell, and Condoleezza Rice.

While the contributions of so many provide insight to the progress we have made, it is the contributions of a few that are truly quite remarkable.

The following are ten African-Americans who changed our nation for their advocacy, scholarship, and an unbridled desire to make positive change that will reap dividends well beyond their lifetimes.

We hope the stories you will find below to be encouraging, uplifting, and will inspire you to live for positive change.

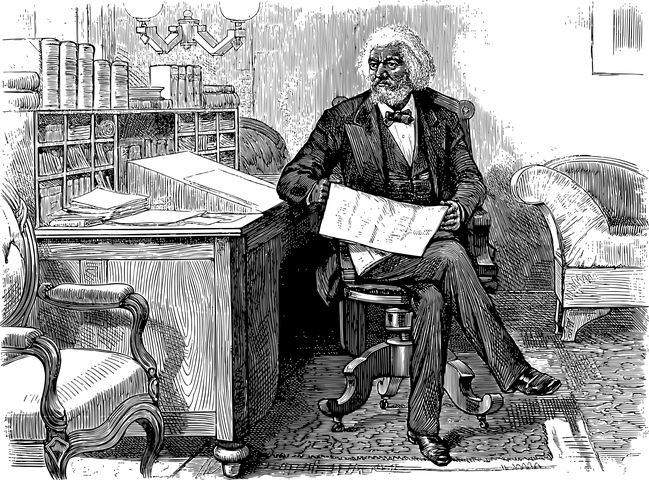

1. Frederick Douglass – American Abolitionist (1817-1895)

Born in Talbot County, Maryland, he was sent to Baltimore as a house servant at the age of eight, where his mistress taught him to read and write. Upon the death of his master he was sent to the country to work as a field hand. During his time in the South he was severely flogged for his resistance to slavery. In his early teens he began to teach in a Sunday school which was later forcibly shut down by hostile whites. After an unsuccessful attempt to escape from slavery, he succeeded in making his way to New York disguised as a sailor in 1838. He found work as a day laborer in New Bedford, Massachusetts, and after an extemporaneous speech before the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society became one of its agents.

Douglass quickly became a nationally recognized figure among abolitionists. In 1845, he bravely published his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, which related his experiences as a slave, revealed his fugitive status and further exposed him to the danger of reenslavement. In the same year he went to England and Ireland, where he remained until 1847, speaking on slavery and women’s right and ultimately raising sufficient funds to purchase his freedom. Upon returning to the United States he founded the North Star. In the tense years before the Civil War he was forced to flee to Canada when the governor of Virginia swore out a warrant for his arrest.

Douglas returned to the United States before the beginning of the Civil War and after meeting with President Abraham Lincoln he assisted in the formation of the 54th and 55th Negro regiments of Massachusetts. During Reconstruction he became deeply involved in the civil rights movement and in 1871 he was appointed to the territorial legislature of the District of Columbia. He served as one of the presidential electors-at-large for New York in 1872 and shortly thereafter became the secretary of the Santo Domingo Commission. After serving for a short time as the police commissioner of the District of Columbia, he was appointed marshal in 1871 and held the post until he was appointed the recorder of deeds in 1881. In 1890 his support of the presidential campaign of Benjamin Harrison won him his minister resident and consul general to the Republic of Haiti and later, the charge d’affaires of Santo Domingo. In 1891, he resigned the position in protest of the unscrupulous business practices of American businessmen. Douglass died at home in Washington, D.C. (Reprinted from The Gale Group)

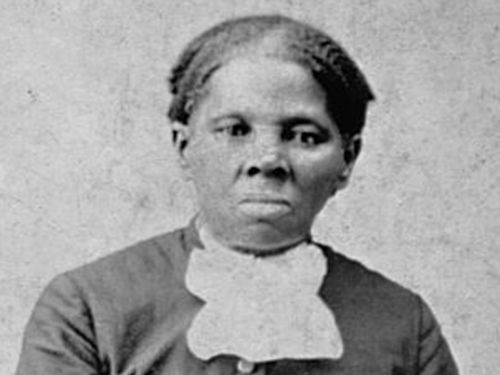

2. Harriet Tubman – American Abolitionis (1820-1913)

Born in 1820 in Dorchester County, Maryland, Harriet Tubman had the hard childhood of a slave: much work, little schooling, and severe punishment. In 1848, she escaped, leaving behind her husband John Tubman, who threatened to report her to their master.

As a free woman, she began to devise practical ways of helping other slaves escape. Over the following 10 years she made about 20 trips from the North into the South and rescued more than three hundred slaves. Her reputation spread rapidly, and she won the admiration of leading abolitionists (some of whom sheltered her passengers). Eventually a reward of $40,000 was posted for her capture.

Tubman met and aided John Brown in recruiting soldiers for his raid on Harpers Ferry. Brown referred to her as “General Tubman”. One of her major disappointments was the failure of the raid, and she is said to have regarded Brown as the true emancipator of her people, not Lincoln. In 1860 she began to canvass the nation, appearing at anti-slavery meetings and speaking on women’s rights.

Shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War, she was forced to leave for Canada, but she returned to the United States and served the Union as a nurse, soldier, and spy; she was particularly valuable to the army as a scout because of the knowledge of the terrain she had gained as a conductor on the Underground Railroad.

Tubman’s biography (from which she received the proceeds) was written by Sarah Bradford in 1868. Tubman’s husband, John, died two years after the end of the war, and in 1869 she married the war veteran Nelson Davis. Despite receiving many honors and tributes (including a medal from Queen Victoria), she spent her last days in poverty, not receiving a pension until 30 years after the Civil War. With the $20 dollars a month that she finally received, she helped to found a home for the aged and needy, which was later renamed the Harriet Tubman Home. She died in Auburn, New York. (Reprinted from The Gale Group)

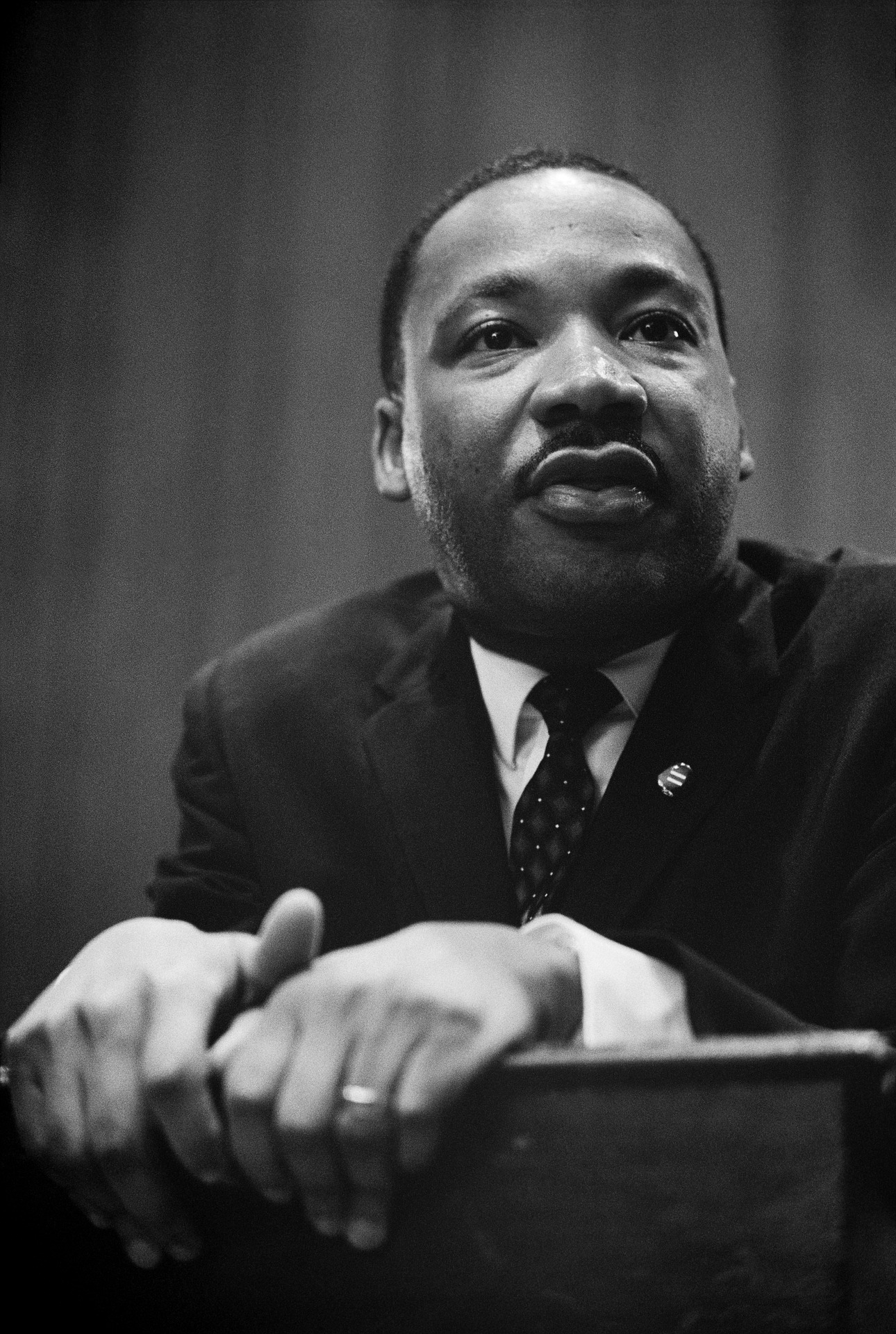

3. Martin Luther King, Jr. – American Minister (1929-1968)

Martin Luther King Jr. was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. An African-American church leader and a son of early civil rights activist and minister Martin Luther King Sr., King advanced civil rights for people of color in the United States through nonviolence and civil disobedience. Inspired by his Christian beliefs and the nonviolent activism of Mahatma Gandhi, he led targeted, nonviolent resistance against Jim Crow laws and other forms of discrimination.

King participated in and led marches for the right to vote, desegregation, labor rights, and other civil rights. He oversaw the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott and later became the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). As president of the SCLC, he led the unsuccessful Albany Movement in Albany, Georgia, and helped organize some of the nonviolent 1963 protests in Birmingham, Alabama. King was one of the leaders of the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The civil rights movement achieved pivotal legislative gains in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Sadly, he was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee on April 4, 1968. (Reprinted from Wikipedia)

4. Rosa Parks – American Activist (1913-2005)

According to the old saying, “some people are born to greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them.” Greatness was certainly thrust upon Rosa Parks, but the modest former seamstress has found herself equal to the challenge. Known today as “the mother of the Civil Rights Movement,” Parks almost single-handedly set in motion a veritable revolution in the southern United States, a revolution that would eventually secure equal treatment under the law for all black Americans. “For those who lived through the unsettling 1950s and 1960s and joined the civil rights struggle, the soft-spoken Rosa Parks was more, much more than the woman who refused to give up her bus seat to a White man in Montgomery, Alabama,” wrote Richette L. Haywood in Jet. “[Hers] was an act that forever changed White America’s view of Black people, and forever changed America itself.”

From a modern perspective, Parks’s actions on December 1, 1955 hardly seem extraordinary: tired after a long day’s work, she refused to move from her seat in order to accommodate a white passenger on a city bus in Montgomery. At the time, however, her defiant gesture actually broke a law, one of many bits of Jim Crow legislation that assured second-class citizenship for blacks. Overnight Rosa Parks became a symbol for hundreds of thousands of frustrated black Americans who suffered outrageous indignities in a racist society. As Lerone Bennett, Jr. wrote in Ebony, Parks was consumed not by the prospect of making history, but rather “by the tedium of survival in the Jim Crow South.” The tedium had become unbearable, and Rosa Parks acted to change it. Then, she was an outlaw. Today she is a hero. (Reprinted from The Gale Group)

5. Thurgood Marshall – Supreme Court Justice (1908-1993)

United States Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall built a distinguished career fighting for the cause of civil rights and equal opportunity. Ebony dubbed Marshall “the most important Black man of this century — a man who rose higher than any Black person before him and who has had more effect on Black lives than any other person, Black or White.” The first African-American to serve on the Supreme Court, Marshall stood alone as the Supreme Court’s liberal conscience toward the end of his career, the last impassioned spokesman for a left-wing view on such causes as affirmative action, abolishment of the death penalty, and due process. His retirement in 1991 left the Court in the hands of more conservative justices.

Duke University professor John Hope Franklin told Ebony: “If you study the history of Marshall’s career, the history of his rulings on the Supreme Court, even his dissents, you will understand that when he speaks, he is not speaking just for Black Americans but for Americans of all times. He reminds us constantly of the great promise this country has made of equality, and he reminds us that it has not been fulfilled. Through his life he has been a great watchdog, insisting that this nation live up to the Constitution.” (Reprinted from The Gale Group)

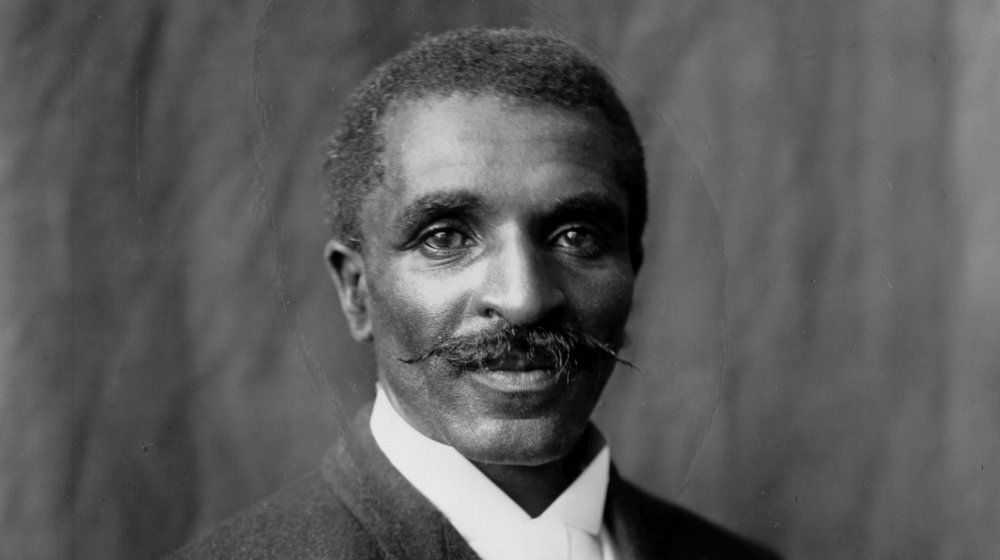

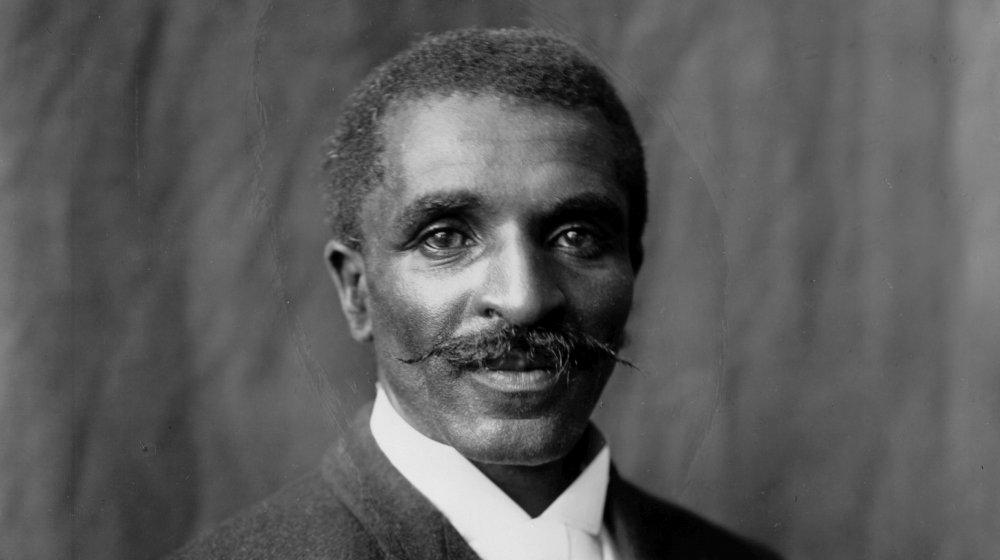

6. George Washington Carver – American Agricultural Scientist (1864-1943)

George Washington Carver devoted his life to research projects connected primarily with southern agriculture. The products he derived from the peanut and the soybean revolutionized the economy of the South by liberating it from an excessive dependence on cotton.

Born a slave, Carver revolutionized the southern agricultural economy by showing that 300 products could be derived from the peanut. By 1938, peanuts had become a $200 million industry and a chief product of Alabama. Carver also demonstrated that 100 different products could be derived from the sweet potato.

Although he did hold three patents, Carver never patented most of the many discoveries he made while at Tuskegee, saying “God gave them to me, how can I sell them to someone else?” In 1938 he donated over $30,000 of his life’s savings to the George Washington Carver Foundation and willed the rest of his estate to the organization so his work might be carried on after his death. He died on January 5, 1943. (Reprinted from The Gale Group)

7. Barack Obama – 44th U.S. President (1961 – )

His story is the American story — values from the heartland, a middle-class upbringing in a strong family, hard work and education as the means of getting ahead, and the conviction that a life so blessed should be lived in service to others.

With a father from Kenya and a mother from Kansas, President Obama was born in Hawaii on August 4, 1961. He was raised with help from his grandfather, who served in Patton’s army, and his grandmother, who worked her way up from the secretarial pool to middle management at a bank.

After working his way through college with the help of scholarships and student loans, President Obama moved to Chicago, where he worked with a group of churches to help rebuild communities devastated by the closure of local steel plants.

He went on to attend law school, where he became the first African-American president of the Harvard Law Review. Upon graduation, he returned to Chicago to help lead a voter registration drive, teach constitutional law at the University of Chicago, and remain active in his community.

President Obama’s years of public service are based around his unwavering belief in the ability to unite people around a politics of purpose. In the Illinois State Senate, he passed the first major ethics reform in 25 years, cut taxes for working families, and expanded health care for children and their parents. As a United States Senator, he reached across the aisle to pass groundbreaking lobbying reform, lock up the world’s most dangerous weapons, and bring transparency to government by putting federal spending online.

He was elected the 44th President of the United States on November 4, 2008, and sworn in on January 20, 2009. (Reprinted from The Gale Group)

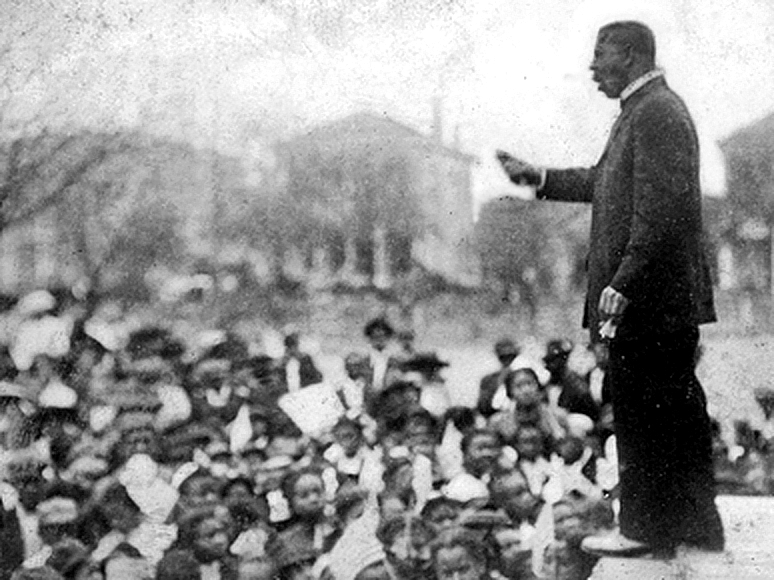

8. Booker T. Washington – American Educator (1856-1915)

Booker T. Washington was born a slave in Hale’s Ford, Virginia, reportedly on April 5, 1856. After emancipation, his family was so poverty stricken that he worked in salt furnaces and coal mines beginning at age nine. Always an intelligent and curious child, he yearned for an education and was frustrated when he could not receive good schooling locally. When he was 16 his parents allowed him to quit work to go to school. They had no money to help him, so he walked 200 miles to attend the Hampton Institute in Virginia and paid his tuition and board there by working as the janitor.

Dedicating himself to the idea that education would raise his people to equality in this country, Washington became a teacher. He first taught in his hometown, then at the Hampton Institute, and then in 1881, he founded the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama. As head of the Institute, he traveled the country unceasingly to raise funds from blacks and whites both; soon he became a well-known speaker.

His major achievement was to win over diverse elements among southern whites, without whose support the programs he envisioned and brought into being would have been impossible.

In addition to Tuskegee Institute, which still educates many today, Washington instituted a variety of programs for rural extension work, and helped to establish the National Negro Business League. Shortly after the election of President William McKinley in 1896, a movement was set in motion that Washington be named to a cabinet post, but he withdrew his name from consideration, preferring to work outside the political arena. (Reprinted from The Gale Group)

9. Sojourner Truth – American Abolitionist (1797-1883)

Born Isabella Baumfree in Ulster County, New York, around 1797, she was freed by the New York State Emancipation Act of 1827 and lived in New York City for a time. After taking the name Sojourner Truth, which she felt God had given her, she assumed the “mission” of spreading “the Truth” across the country.

She became famous as an itinerant preacher, drawing huge crowds with her oratory (and some said “mystical gifts”) wherever she appeared. She became one of an active group of black women abolitionists, lectured before numerous abolitionist audiences, and was friends with such leading white abolitionists as James and Lucretia Mott and Harriet Beecher Stowe.

With the outbreak of the Civil War she raised money to purchase gifts for the soldiers, distributing them herself in the camps. She also helped African Americans who had escaped to the North to find habitation and shelter. Age and ill health caused her to retire from the lecture circuit, and she spent her last days in a sanatorium in Battle Creek, Michigan. (Reprinted from The Gale Group)

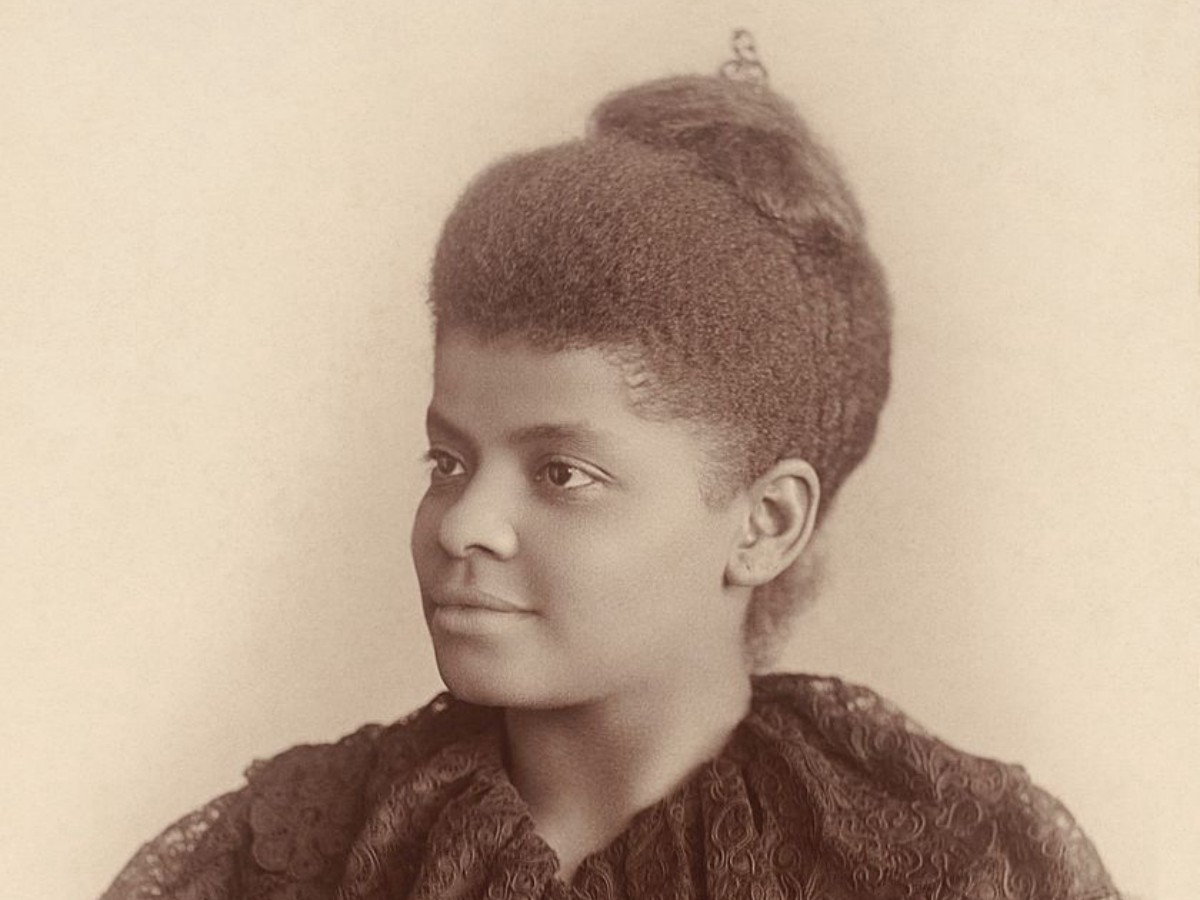

10. Ida B. Wells – American Journalist (1862-1931)

Born July 16, 1862, in Holly Springs, Mississippi, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was a former slave who became a journalist and launched a virtual one-woman crusade against the vicious practice of lynching.

Activist and journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett was an early proponent of civil rights. Editor and partial owner of her own newspaper, she published articles on topics considered controversial at the time. One of her main causes was fighting the practice of lynching, which she regarded as a horrific form of racial prejudice that no decent human being could ignore or justify. For years, the vicious practice of lynching had been widely used — especially in the South after the Civil War — as a means of punishing alleged criminals, although two-thirds of the victims were African American. The word “lynching” dates back to the late 1700s, when a frontier judge named Charles Lynch became known for dispensing with jury trials in favor of speedy hangings. These came to be known as “lynchings,” and they later evolved into acts of mob violence in which someone was put to death, usually by hanging. Wells-Barnett waged her war against it in the press as well as on the podium, earning a reputation for fearlessness and determination despite numerous efforts to intimidate her, including death threats.

She died March 25, 1931. (Reprinted from The Gale Group)

Editors Note: All images used in this article are in the public domain with the exception of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Barack Obama which come from Pixabay.