Thoughts on Writing a Memoir, & the Prologue to “Rosaries, Reading, Secrets” | Dreaming Beneath the Spires

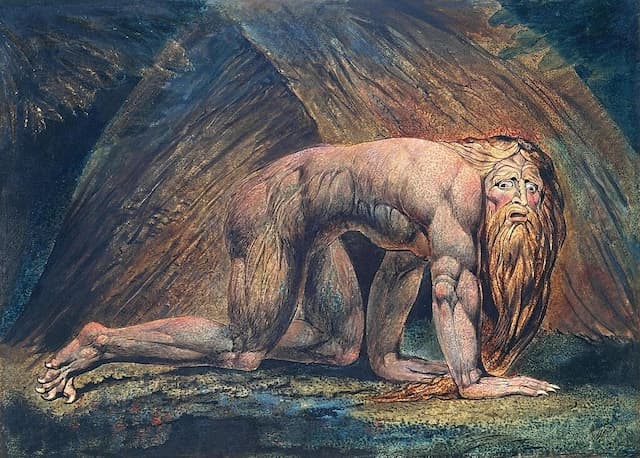

Writing a memoir awakens fierce memories of the past. For the past is not dead; it’s not even past, as William Faulkner observed. So what does one do with this undead past? Forgive. Forgive, huh? Forgive. Let it go. Again and again. For, after all, this world is one of insistent goodness, insistent abundance. Flowers bloom in the desert and, now, even in Antarctica. Plough a field in the English countryside, leave it fallow, and lo, it’s populated–the purple of thistles, belladonna and morning glories, the gold of buttercups and dandelions. Royal colours.

Little is wasted. We are recycled from exploded stars. Seeds look like unpromising things, hard and black. But they bring forth sunflowers and mighty mango trees; they sustain life itself. So I drop the past into the hands of God and trust him to bring from it something different and better as seeds bring forth surprises–roses perhaps, or pomegranates, forming the stuff of humans and elephants, of all this mighty world. Scientists germinated a thirty-two-thousand-year-old ice age seed in Siberia which flowered. So forgiveness is also this: to drop past pain into a greater hand, again and again, and ask him to make it bloom, even now, decades later.

Prologue to Rosaries, Reading, Secrets: A Catholic Childhood in India

In the Beginning:

You Woke and Heard the Birds Cough

I was made in India, in Jamshedpur, in Bihar then, (Jharkhand now), where the great Gangetic plains lope up to the foothills of the Himalayas.

The Buddha achieved enlightenment there in Bihar, six centuries before Christ; Mahavira, founder of Jainism, was born there. But I was an accidental pilgrim in this birthplace of religions. I was born in Jamshedpur because of steel.

The soil was red-ochre, flecked with tiny balls of murram, iron ore, visible signs of the hidden lodes which, in 1907, drew Zoroastrian industrialist, Jamshedji Nusserjani Tata, to Bihar to found Jamshedpur, The Steel City.

In Jamshedpur, blast furnaces belched grimness into the bleared skies as iron ore was refined to shining steel by The Tata Iron and Steel Company, one of the world’s largest steel companies, which, in 1952, lured my father, a Chartered Accountant, from still-racist London. (“Our accountant is Indian; is that a problem?” his boss had to ask. Sometimes it was.) Now he was the Controller of Accounts at Tata’s—and after he visited Pittsburgh in the sixties and introduced the first computers to TISCO, monsters which hogged a wall, he also became Manager of Data Processing, as I told everyone proudly. And “What is that?” they asked.

My father married late, aged thirty-eight. I was born after seven years of infertility and the death of their infant first-born son, Gerard, three days old. My mother never overcame her disappointment that I, born the year after Gerard, was a mere girl, while my father, who’d mournfully say that girls were a terrible thing, expected me to be every bit as extraordinary as the boy who never lived would undoubtedly have been.

Within hours of my birth, I fell ill with dysentery, which had killed my elder brother. My father vowed he would go to Mass every Friday for ten years if I lived. I did; he did. And so, in an emergency baptism with hastily-blessed hospital water, in Jamshedpur, at the heart of the Hindu heartland, I was christened Anita Mary Mathias, daughter of Noel Joseph Mathias and Celine Mary Mathias, the European surname given to our family when the Portuguese occupied my ancestral town of Mangalore on the coast of the Arabian Sea in 1510, converting the population to Roman Catholicism with the carrot of government jobs, and the stick of the Inquisition—Counter-Reformation fires reaching the tropics.

Which explains why a child born in the Hindu heartland had grandparents called Piedade Felician Mathias and Josephine Euphrosyne Lobo, Stanislaus Coelho and Molly Rebello, and great-grandmothers called Gracia Lasrado Mathias, Julianna Saldanha Lobo, Alice Coelho Rebello and Apolina Saldanha Coelho, though, on my mother’s side, everyone was a Coelho, for Coelhos, as the thirteen branches of that family observe proudly, Coelhos, whenever possible, only marry Coelhos.

Thanks for reading, friends. I’d be grateful for your support. Available at amazon.com and amazon.co.uk