Two powers (Matthew 21–28)

Kings and priests were both anointed in the OT. How does this conflict of powers play out in Matthews’ Gospel? It goes to the heart of his explanation of the cross.

Once you realize the gospel is the good news of the kingdom (with Jesus as the anointed king), you see how the latter part of Matthew’s Gospel is the conflict of the two positions anointed by God: high priesthood and kingship. Matthew 21–28 chronicles the outworking of that clash.

Anticipating the conflict (Matthew 1–20)

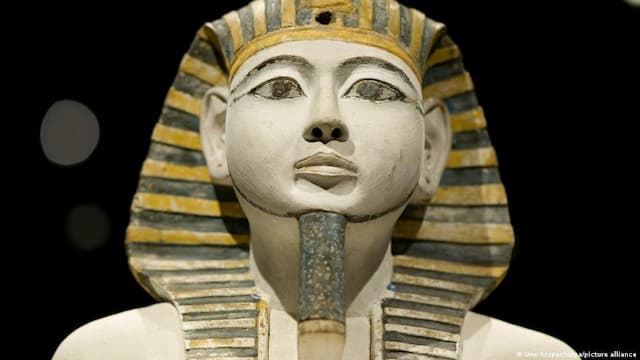

When Matthew introduces Jesus as anointed son of David, it’s a kingship claim (1:1). But priests were also anointed. As servants of God’s house, they also represented heaven’s authority on earth. In the Old Testament story there had been significant clashes between the two powers. Declaring Jesus to be God’s Anointed therefore raised red flags for the high priest who saw himself as God’s anointed.

Foreigners can recognize the one who is born king of the Jews (2:2), but for Herod another king is a rival (2:13). And the high priests are not aligned with God’s Messiah; they’re informing the ruler who drives the child into exile (2:4). Jerusalem is not a safe place for Jesus even after Herod’s death, since Archelaus reigns in his father’s place (2:22). It sounds like more than verbal similarity between Archelaos (the king’s name) and the archiereus (high priest). Jesus’ purification and anointing in the wilderness (3:1-17) probably reflect the kind of distrust of the temple found at Qumran.

The second reference to the high priest comes when Peter declares Jesus to be God’s anointed. Jesus explains the clash this produces:

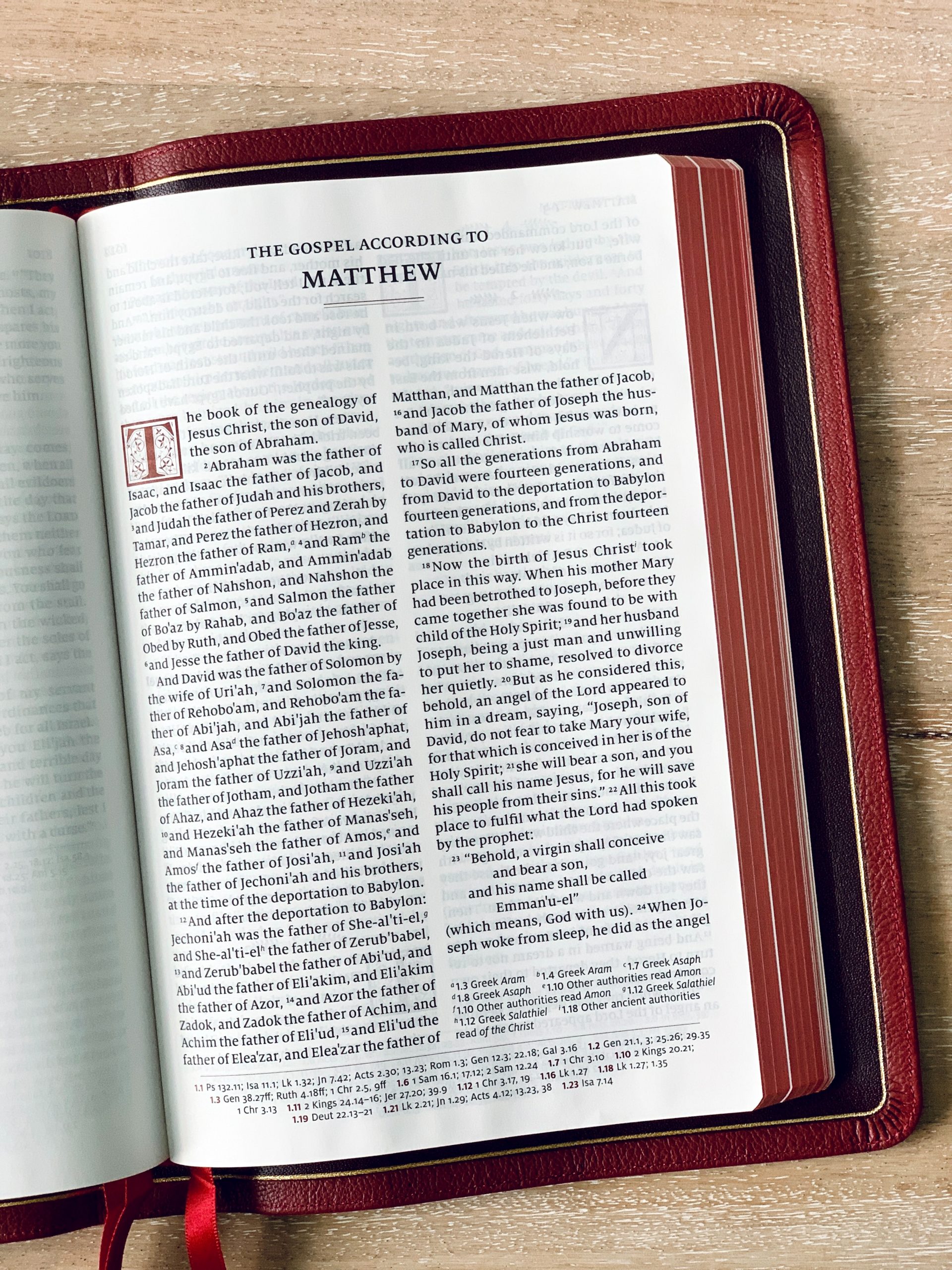

Matthew 16:20–21 (NIV)

20 Then he ordered his disciples not to tell anyone that he was the Messiah. 21 From that time on Jesus began to explain to his disciples that he must go to Jerusalem and suffer many things at the hands of the elders, the chief priests and the teachers of the law, and that he must be killed and on the third day be raised to life.

Deadly conflict is inevitable when the son of man goes to the capital to receive the kingdom. The temple authorities will betray him to the nations to have him executed (20:17-19).

The conflict goes public (Matthew 21)

Jesus does nothing to avoid this conflict. He rides into Jerusalem on a donkey, invoking Zechariah’s promise of the return of the king (Matthew 21:5). Zechariah was all about the post-exilic restoration of the two authorities anointed by God, the two who are anointed to serve the Lord of all the earth (Zech 4:14).

The temple had been restored, with the high priest Joshua anointed in 515 BC. The kingship had not: Zerubbabel (descendant of King David) was told to wait. For that time, the crown was given to the high priest to fulfil the role of Davidic Branch also — two roles harmonized in one person (Zech 6:11-13). It wasn’t the long-term solution: one day the king would ride into Jerusalem to restore the kingdom (Zech 9:9).

When that day came, the high priest had held the crown so long that he was not about to let go. Far from being anointed by God to care for his house, the temple was a den of thieves grasping power for themselves. The king overturned the temple. Having the crowd support the king infuriated the temple (Matthew 21:12-15).

The conflict between the two authorities escalates from here. The temple questions the king’s authority (21:23-27). The king declares that the other son will not enter his kingdom (21:28-32). He says they will lose their place as God’s servants if they kill his Son (21:33-44). They knew he was talking about them (21:45).

The king condemns the temple (Matthew 22–23)

The king told them the heavenly sovereign would throw out those who refused to celebrate his Son (22:1-14). With Solomonic wisdom, he avoided the traps they set for him (22:15-40). He silenced their objections with the declaration of Psalm 110 that God would bring the enemies of the king under his feet (22:41-45).

While acknowledging the priesthood as a genuine authority rooted in the Torah, the king said the present leaders were not serving God or caring for his people (23:1-4). He exposed them as actors with roles based solely on human recognition (23:5-12). He announced their downfall: in rejecting the king, they shut the door of the kingdom of heaven in people’s faces (23:13). It’s meaningless to claim the temple’s authority without recognizing the God who reigns there (23:16-22). Their authority comes not from God but from Death — killing those who do speak for God, so they can stay in power (23:27-32).

The leadership of Death can only take God’s people to disaster (23:33-36). The king had tried to gather them under his leadership, but there is no rescue for those refuse to follow the one anointed by heaven (23:39, compare 21:9).

A temple occupied by bandits cannot survive. What happened in Jeremiah’s time would recur. When he spoke of the desolation of God’s house (23:38), he meant it would be torn down, stone by stone (24:2).

The Olivet Discourse (Matthew 24) continues these twin themes: a) the demise of the temple and the suffering it causes, and b) the reign of the Son of Man who brings heaven’s authority back to earth. We’ll cover that in another post.

The temple condemns the king (Matthew 26)

The conflict between temple and kingship turns deadly when the high priest hosts a meeting at his residence to plot the death of the king (26:4). Tragically, one of those whom Jesus had appointed to judge the twelve tribes of Israel (19:28) joins the plot to bring down the king (26:14).

The temple will kill the king. Jesus says this by reusing a text on how the death of King Josiah left God’s flock unprotected, scattered in exile (26:31, Zechariah 13:7).

But even in this most dire moment, Jesus does not seek reinforcements against the temple. He seeks the only genuine source of authority, his Father. He seeks God not in the temple, but in a garden (26:36).

Jesus had never initiated the label sinner on anyone, but he does now (26:45). Sinners are those who resist God’s authority: the chief priests and elders whose authority comes from being armed with swords and clubs (26:47, 55).

When he chose the servant of the high priest as his target, Peter knew the conflict was temple versus kingship (26:51). Jesus rejected violence as the path to power: all who take up the sword will destroy themselves with the sword (26:52). He rejected using even the forces of heaven to save himself and the eleven (26:53), since the revelation of God’s character comes in giving life to his Son, not death to this enemies (26:54, 56).

Conversely, the temple was looking for false evidence against Jesus so they could put him to death (26:59). The allegations against him map precisely to the two facets of temple/kingship conflict:

- He spoke against the temple (26:61).

- He claimed to be king (26:63).

The capital charge of blasphemy sticks only if we presume that a) the temple speaks for God (so Jesus speaking against the temple is speaking against God), and b) Jesus’ claim to be God’s anointed is bogus (26:65).

In this power contest, Jesus lost. Even Peter disowns him. There is no one whom Jesus can acknowledge before his Father’s throne (26:69-75, compare 10:32-33).

So, who has the authority? (Matthew 27–28)

With the high priests planning the king’s execution (27:1), Judas’ alliance with the temple dissolves. He realizes he has sided with death (27:5).

The high priests hand over the king to their enemies. Even the Romans can see that it was out of self-interest that they handed Jesus over (27:18). The temple misrepresents God to the Empire when they call for the release of a killer and condemn the innocent (27:20-24).

Imperial power serves death also (22:24, 26). God’s people have suffered through the centuries because the kings of the earth rise up and the rulers band together against the Lord and against his anointed, saying, ‘Let us break their chains and throw off their shackles’ (Psalm 2:2-3). Now the temple has joined their enemies, inspiring the solders to mock the King of the Jews (27:29, 37). The temple leaders scorn Jesus’ faith that God would raise him up, treating the crucifixion as evidence that God rejected him (27:43).

That is how it looks and feels, even to Jesus (27:46). God has not intervened. The Messiah dies. The temple stands.

But, wait! At the moment when the Spirit-anointed Messiah gave up his spirit (27:50), the partitioning curtain of the temple was split from above, all the way down, into two pieces (27:51). God tore open the temple.

Something is wrong if the temple feels the need to guard the power of death (27:64). They labelled Jesus a deceiver (27:63), but when God raises him up the temple is revealed as the deceiver (28:12).

At the end of Matthew’s Gospel, the temple has no authority. All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to the king who trains the nations to obey what he commands through the enduring presence that empowers his servants (28:18-21).

Conclusion

The kingship of the Christ is Matthew’s main message. How he dealt with the other institution that claimed to be anointed by God — the temple — is crucial to how he received the kingship.

Matthew is on-track with his Gospel. The gospel is not a story about me and how I can get my piece of forgiveness; it’s a story about Jesus and how he rescues God’s world. Matthew was right to summarize the gospel Jesus proclaimed as the good news of the kingdom (4:23; 9:35; 24:14).

That’s the gospel the apostles proclaimed in Acts, that Jesus Christ is Lord, that God’s anointed is raised and reigning as heaven’s authority over the earth. This global reconfiguration of authority rescues the world from the powers of evil and death, so it can function as God intended, as the temple where our heavenly sovereign lives among his people.

So, next time we’ll see what happens when we read Matthew 24 in the context of the temple/kingship conflict.

Related posts

- Matthew’s main message

- Woe there: how did Jesus treat his enemies? (Mt 23)

- What does ‘Son of God’ mean? (Mt 16:16)

- Who wears the crown? (Zech 6)

Seeking to understand Jesus in the terms he chose to describe himself: son of man (his identity), and kingdom of God (his mission). Riverview Church, Perth, Western Australia

View all posts by Allen Browne