The Theology of Jen Hatmaker, With Anne Kennedy—The Alisa Childers Podcast #52

I'm happy to welcome Anne Kennedy back to the podcast to discuss her impressions of the beliefs, worldview, and theology of Jen Hatmaker. After reading her books and listening to a year's worth of podcasts, Anne helps us understand what Hatmaker is communicating about the cross, the gospel, and the Bible.

*Please excuse the background noise…Anne is a rockstar for doing this podcast while her six kids are home on summer vacation!

Transcript:

Alisa: Anne Kennedy has just done some extensive research into the beliefs, the worldview and the theology of Jen Hatmaker. She’s written an article for the Christian Research Journalcalled “The Theology of Jen Hatmaker.” Anne, from what I understand, you spent a year listening to Jen’s podcast. Is that right?

Anne: Well, I crammed a year into about three months. It was pretty intense.

Alisa: I can imagine. This was all part of some research you did for this article in the Christian Research Journal. My exposure to Jen Hatmaker goes back I believe to somewhere around 2008 or 2009. A friend of mine was going to be doing a book study in her home, and she told me, “I think you’d be perfect for this one, Alisa. It’s a little outside the lines, but I think you’ll dig it.”

I came to the meeting, where we were going to be going through one of Jen’s books—I honestly can’t remember which one. I hadn’t heard of her, but I remember being immediately gripped by her writing. She has a way of writing like that inner monologue we sometimes experience. It’s so relatable, and I was instantly drawn in by her style. At the same time, I was troubled by what I was reading.

At the time, I hadn’t really studied theology and apologetics yet, so I couldn’t articulate what was bothering me. The best I could identify what was troubling me wasn’t what she was saying, but what she wasn’t saying. She was focusing on things that were fine—I couldn’t say they were heretical or theologically terrible. I just remember thinking there was so much missing. Now I realize what was missing was a robust gospel—the idea of what Jesus came to do and why He died.

I ended up leaving the study before it was done. This was before my faith crisis, and it was when the Progressive thing was just entering the mainstream. A lot of evangelicals were reading Jen Hatmaker and Brian McLaren and others, but it hadn’t gone too far off the rails yet. Of course, a few years ago Jen Hatmaker sent shock waves through the evangelical world, because—as a self-proclaimed evangelical—she changed her mind on the LGBTQ issue. She affirmed same-sex relationships, and she has been on that trajectory ever since.

Anne, I’m thrilled to talk with you about her theology, because I honestly haven’t dug that deep into what she believes. I’ve seen some Facebook posts and read a little of one of her books, but that’s about it. So I want to pick your brain today about the theology of Jen Hatmaker. I think it’s important because so many otherwise theologically sound Christians are following her because she’s funny and engaging. She writes funny things about her kids.

Even after she shifted on the LGBT issue, many of them continued to follow her, so she’s very influential. Last time I checked on Facebook, she had close to a million followers. This isn’t just someone off in a corner—she is truly influencing the evangelical world. So, Anne, I’m thrilled to see writers like you addressing some of these things. Please give us some initial thoughts about the theology of Jen Hatmaker.

Anne: She is very engaging. I enjoy reading her books a lot, and she’s a good podcaster. She interviews a lot of people who are kind of on the Progressive side. But I found that she does not have a new reading of the Bible. The main thing that really troubled me as I read through her stuff was something I think she took from Barbara Brown Taylor and others, and that is that she recasts the meaning of holiness.

Holiness should apply to things that are set apart by God. God is holy, and He can make people and things holy by setting them apart. But Jen confuses this with the common stuff of life that is just really good. If you have a really lovely experience with someone—if you have a great meal and conversation—she says that experience can be holy. Or if you rearrange your living room and it becomes more hospitable and welcoming, that could be holy. She blurs the line, which I’ve seen other people do as well.

Thus God is brought very close and becomes kind of confused with our stuff. She uses words like holy and sanctuary and altar and church, but she doesn’t use them precisely. Rather, they’re used in a fuzzy way to mean whatever your doing that you find helpful right now. That’s troublesome, because you can take that and then give yourself permission to do things that are not allowable—not holy.

One of the things that’s really attractive about what she says is that she gives women permission to not be perfect—and that is a huge reason why she resonates with so many people. She gives women permission to let themselves off the hook for the difficulties of their lives. Many women who are at home with their children or are isolated and struggling and unhappy need to be told it’s okay that they’re not good enough. But they don’t need to told that they’re holy.

Listening to her, I don’t think she has grasped the actual definition of holiness. I found that really troubling. Then of course, if you don’t have the holiness of God, then you’re not set up to understand the gospel. It just isn’t going to make sense to you. You’re not going to be able to distinguish between the law the gospel in any meaningful sense. That’s where she steps up right away to go off the rails.

Alisa: That’s an interesting point, because this is something I’ve noticed as a trend in Progressive thought. The Progressive author or thought leader will take a word and redefine the word—but not give any source. They’ll make the statement, “Holiness means this,” and then build an entire theology around their definition that really has no basis in objective truth.

A good example of this is Nadia Bolz Weber in her book Shameless: A Sexual Reformation. She defines holiness like this. “Holiness is the union we experience with one another and with God. Holiness is when more than one become one—what is fractured is made whole.”

This is a completely random and subjective definition of holiness. Obvious, holiness actually implies separateness and being set apart. God is entirely separate from sin, yet she says holiness is more about union. That’s why, a couple chapters later, she can call a one night stand holy.

In fact, Richard Rohr does this with the word “faith.” He defines faith as “walking in darkness,” so then he can pit certainty and faith against each other, as though they’re opposites. But there’s no effort to go to the Hebrew or Greek to support this. He just declares, “This is what it means,” and then he builds his entire theology based on an entirely subjective definition. It sounds like that’s what’s going on with Jen’s definition of holy as well.

Anne: Yeah, it feels normal and fine to say what she does. There’s a sort of transcendent, numinous feel when you’re with someone you love, so that must be from God. When you line that alongside the Scripture, then the Bible won’t really make any sense. All of the commands relating to holiness become completely incomprehensible. The people of Israel were supposed to be set apart. They did not have union with God—that was the problem that God was going to correct. It wasn’t by them just being with Him, but by Him making them holy in order that they could be with Him.

Then of course that drives us to the cross. But that’s the other thing—Jen doesn’t have a theology of the cross. Like so many others, she says Jesus died because He loved so much.

Alisa: It’s as though He submitted to death, but it wasn’t His salvific plan.

Anne: Right. It’s as though we just don’t love love enough. Jesus loved love so much that He was willing to die for it. If only we could love love as much as He loved love, we’d be willing to sacrifice ourselves in the way He did. The whole business of Jesus being the holy and perfect sacrifice for sin is completely gone. It’s not even there. She’s not able to make sense of the cross at all.

I’m finding that her definition of salvation is really something like human encouragement. You can save another person by encouraging them a lot, then they’ll receive enlightenment. They’ll get their head in the right place and realize that love is love, and then they’ll behave the way they’re supposed to behave—which is to be very encouraging.

Alisa: Did you hear her talk at all about substitutionary atonement or anything like that? Does she outright deny it—or is she coming at it more like she’s not really sure?

Anne: I’m pretty sure she doesn’t mention it. When she talks about Jesus, it doesn’t come up. I can’t stake my life on that, but I can’t remember any place where she does mention it. She mentions the cross, but it’s in a vague sort of way.

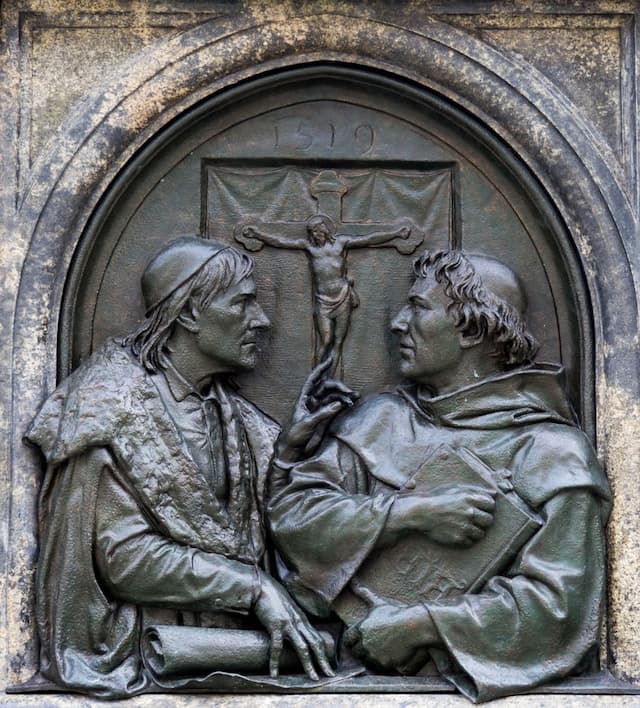

Alisa: Let me read a quote from her interview with Richard Rohr, who is heavily influential in the Progressive world. I think he’s actually becoming the grandfather of the Progressive movement in a way. She says in the interview that she has quoted him in her books, and she calls him a spiritual father and mentor. She’s very much a follower of Richard Rohr. Here’s what he says about the cross in an article about substitutionary atonement:

I believe that Jesus’ death on the cross is a revelation of the infinite and participatory love of God, not some bloody payment required by God’s offended justice to rectify the problem of sin. Such a story line is way too small and problem oriented.

Then in a video he posted on YouTube, Rohr said, “Jesus came to change the mind of humanity about God. There was no transaction necessary. There was not a blood sacrifice necessary.” So the man whom Jen calls a spiritual father outright denies the atonement of Jesus. So I’m sure there’s a trickle-down effect there affecting her theology as well, even if she doesn’t articulate it quite as clearly.

Anne: I don’t think she said anything that clearly. She essentially says Jesus came to overturn the law and to overturn our ideas about God, rather than saying He came to fulfill the law or do something humanity couldn’t do. That language was completely absent for her.

She doesn’t actually talk a lot about Jesus. That’s another thing that bothered me. It always felt as though she was mentioning Him in passing because she remembered she needed to. The books I read were not deeply rooted in a sense of who Jesus is or the Scripture. I found that really discouraging.

I like it when people are going to give advice about how to live to really ground it in Scripture. But every time she even brought up the question of Jesus, she was, as my mother would say, “numb and vague.” She doesn’t have a Christology or address the atonement. Jesus is a good model. For example, she wrote:

The work of Jesus—He gave honor to a bunch of folks in the right head space, like kids and widows and outsiders. He stayed at parties and dinners. Jesus forgave His enemies while He was hanging on the cross, just to be clear about how forgiveness works pragmatically.

The problem isn’t that we don’t have the right “head space.” We are sinners, and we have the wrong ideas and the wrong actions. That set up her gospel of inclusion, that if you include the outsider and the marginalized, you’re doing what God wants you to do, and He will accept you. By doing that, your work becomes salvific. I would say that’s probably as deep as her gospel goes.

Alisa: It sounds like a works-based gospel.

Anne: I would say it’s very works-based. I really think she trade moral therapeutic deism for progressive therapeutic deism.

Alisa: Let’s unpack that a little bit. For anyone who doesn’t know what it means, what is moral therapeutic deism?

Anne: You find that in sermons that emphasize how you’re supposed to behave as a Christian. You know God wants you to be good, so you end up working really hard to be good—but you never really hear the gospel. You never really understand that you can’t be good, but that Jesus was good on your behalf. He welcomes you into His kingdom on the basis of who He is and what He’s done. He loves you, and your behavior flows out of His actions.

Of course, we’re supposed to do good works. Moral therapeutic deism means that God wants you to be happy, and He wants you to be good. He will give you the power to do both those things if you understand enough about Him. I feel as though this is a very American gospel. Americans like attitude checks and being able to please God with their right attitudes and good behavior.

I think Progressives really rejected that, because they came to feel that God doesn’t really care about your behavior. He just wants you in His kingdom. He just wants you to be welcomed and loved and accepted for who you are. But that is its own strange work, really, because then you have to go through the very great trial of accepting yourself as you are, with your faults, and accepting others. You can agree that people sin to some degree, but that’s never supposed to injure a relationship so much that there’s no way back from it.

I think it makes it very, very hard. It’s an interesting conflation for someone who has met with abuse. How can you say those things are really wrong, or that God really doesn’t want you to be abusive, if you have to accept everyone? So you’re in a bind. Then you’re also working very, very hard at your inclusiveness, at your good work of loving people without any boundaries on that.

Alisa: Does she actually call it the “gospel of inclusion”?

Anne: I don’t she uses that term particularly, but she talks a lot about inclusion and encouragement. Her particular gift is to encourage people, to build them up and make them feel good and okay, to get over their hurts and the difficulties of life, to know they can be enough and that God loves them—rather than cutting people down. I would say that’s great. You need to encourage people. You shouldn’t cut them down.

But the conviction of sin in the Bible is not a bad thing—it’s the gateway to life. If you throw away sin and you throw away holiness, you have no way of inviting people into the life of Christ who makes you holy.

Alisa: It’s really throwing redemption out the window. Now, regarding moral therapeutic deism, the deism aspect of that—which I think a lot of people ascribe to without realizing it—is where God isn’t really involved in your life. He got the whole things started, like winding up a watch, and then steps back. So if I need something from Him and I’ll pray, and He’ll get involved, but it’s part-time.

I think you make an interesting point when you say people are trading moral therapeutic deism for progressive therapeutic deism. Unpack that one a little bit. How would you describe this trade?

Anne: I think in both cases the belief is that God wants you to be happy. That’s where the therapy part comes in. In moral therapeutic deism, you’ll be happy by being good. In the Progressive view, you’ll be happy by being who you are, by discovering your true identity and understanding that God loves you and everything is fine.

But in order to be saved, you have to accept yourself. So if you can’t accept yourself, then you’re doomed. This is a good example of how God can’t help you with an atoning sacrifice. He’s not very powerful. He needs your help. But He’s there for you as a good example. If you want to pray, He’ll probably help you.

It’s a strange exchange, and in neither case do you come to know God in His work. You don’t ever have union. You don’t ever become holy. You don’t come to know Him, and He doesn’t really know you, I would say. It’s very human-centered, and the person and glory of Christ is not important. You being okay and happy is the center, the key. It’s a tragic exchange. I feel like they’ve gone from the frying pan into the fire.

Alisa: It sounds as if when people trade moral therapeutic deism for progressive therapeutic deism, they never really understood the true gospel in the first place.

Anne: I would say that’s absolutely true.

Alisa: I was reading in Pete Enns’ book where he talks about how he grew up. I think the extent of his theological education was he went to Lutheran confirmation classes or something, and then went to an evangelical service in high school, where the guy said, “Raise your hand and come down to the front if you don’t want to go to hell.” Pete Enns said, “I didn’t want to go to hell, so I raised my hand.”

When I hear stories like that, I wonder if the real gospel was ever apprehended in any meaningful way when people trade this American type of gospel for the Progressive gospel. It makes me sad to see that happen. I think in my story of coming out of some really significant doubt, my doubt was actually perpetuated in the Progressive church. Often people describe the Progressive church as a sanctuary for doubts and questions, but for me it was the cause of a deep faith crisis in my life.

Not that the paradigm I grew up in was perfect, but I did have the real gospel given to me—and that was honestly more important than good hermeneutics or learning apologetics or any of that. That’s what kept me. I knew Jesus, and I couldn’t let Him go. It always makes me sad when I hear people describe the gospel in a way that it’s obvious they don’t know what it is or they haven’t experienced it for themselves.

With that, I was going to ask you—in all of the things you’ve read and listened to from Jen, does she have a hermeneutic? Does she have a way she approaches the Bible that she talks about?

Anne: She doesn’t get into it very much, but I think it’s sort of a run-of-the-mill approach where you use love to serve as the measure for everything. What appears to be loving is what you accept, and what isn’t loving, or you don’t think is loving in the Scripture, then you don’t worry about that. I don’t think she ever deals with any particular text closely, so she’s not a deep reader of Scripture.

She takes the modern, 21stcentury definition of love and applies it back over the Scripture and uses the to measure everything else. That will end you up exactly in the place where you can affirm different kinds of sexuality and gender identity and the definition of inclusion which says you should accept somebody completely and totally without any question about who they are or what they’re doing. Jesus is not worried about people coming out of sin. It’s not very deep.

She does interview a lot of people who have thought about the Scripture much more deeply than she has, but she herself doesn’t really articulate a biblical exegetical model that’s coherent.

Alisa: She was interviewed by Pete Enns on his podcast. I mentioned a few minutes ago how he was Harvard trained. He’s really the scholar that’s informing a lot of these more popular figures. He may not be as popular as they are in the evangelical side of things, but he’s really influencing their views. She was on his podcast, and she was saying how she just devours his podcasts—all of his views. So I know she’s influenced by that.

Interestingly, what you’re saying reminds me of a meme I’ve seen go around in Progressive circles. Jesus is standing in front of a group of Bible-thumping evangelicals. They all have their Bibles under their arms and they of course look super-dorky. In the meme, Jesus says to them, “The different between me and you is you use Scripture to determine what love mean, and I use love to determine what Scripture means.”

Anne: Yep! There it is.

Alisa: But of course, that doesn’t work even from just a logic perspective, because then you have to define love—and you’re defining it subjectively. If you’re not getting your definition of love from Scripture, then you’re saying, “Well, this is what love is, and now I’m going to determine what Scripture means through that lens.” It’s entirely subjective, and it might mean something different to different people.

Anne: Yes, it can change completely, based on how you’re feeling at a particular moment. It makes a very weak argument. I can’t understand why people read the Bible with that paradigm.

But I also think it places a really tragic weight on the individual, because this gospel means you have to accept yourself. So much work has to be done for you to be acceptable to you, which means you would then be acceptable to God. That’s a very great burden. People don’t know how to do that. They really don’t know how to accept themselves, because they know deeply that something is very wrong. They need God to accept and change them to become acceptable.

So you have this psychological weight, and that’s where the peppiness comes from. “You can do this!” The “Rah-rah! Keep your spirits up. Be good! Be nice! It’s going to be great!” That’s because I don’t think people really feel great about themselves. That’s a very great work. It’s one thing to be kind to other people, but then to accept your own self without the grace of God to mediate for you is just a horrible burden to put on somebody.

I don’t approve of this gospel. It looks very nice from the outside, but I think it is just really tough to carry the weight of yourself around all the time without having anybody ever lift it off your shoulders and carry it for you.

Alisa: I think it causes unnecessary shame, because if you think about it, it’s really repentance that sets you free from the shame. If we feel shame or conviction over a sin in our life, or we become aware of something about ourselves that is not conformed to the image of Christ, and we repent and turn from that thing, that’s what really sets us free from the shame.

But when we try to do it ourselves, when we say, “Well, I’m just going to accept everything about myself and love myself just as I am,” inevitably you know deep in your soul that there are things about you that need to change, that need to be purified, that need to be conformed to the image of Christ.

When we have this “gospel” of just being nice and being good and defining holiness in this way, I can’t see how that doesn’t leave someone either to complete hardness of heart—because you’re trying to deny what you’re feeling—or just into this unending shame.

Anne: I think it really does. I think that’s one reason you spend so much time expressing your happiness about what you’re doing and who you are—it’s because you don’t feel it inside. So you have to say it. You have to insist that other people rejoice in it. It’s kind of a Disney phenomenon of theology, where you find your true self, and then that’s it—the movie’s over. But then you have to go home and live with yourself forever. It’s just awful.

Jen had Brené Brown on to talk about shame. That was a really fascinating podcast, and it’s on my list to investigate Brené Brown more, because she’s done studies with young girls regarding what causes shame and how you get out from under it. But in every single case, it’s not the gospel. It’s not repentance, which does release you and puts the burden back on God to do the work and make you holy so that you can live with yourself and so you don’t have to think about yourself at all. You can think about other people.

Alisa: I think Brené Brown does claim some type of Christianity. I don’t think she claims to be evangelical. I think she had walked away from Christianity for a while, and then has embraced some form of it again. I haven’t done a deep dive on her either, but I do know that she has a lot of new age sorts of beliefs about what we are as people.

In fact, there’s a quote from one of her books where she talks about your higher self. She says, “I can only conclude our world is in a collective spiritual crisis. Spirituality is recognizing and celebrating that we are all inextricably connected to each other by a power greater than all of us, and that our connection to that power and to one another is grounded in love and compassion.” She goes on to say, “We’re in spiritual crisis, and the key to building a true belonging practice is maintaining our belief in inextricable human connection. That connection to the spirit that flows between us and every other human in the world is not something that can be broken, but our belief in that is constantly tested and repeated.”

She affirms later, I think, that there’s this idea of divine self, which is all kind of a new age idea, that we are all connected. It’s sort of an panentheistic view, that we’re all connected by this force—almost like the force in Star Wars. It binds us all together, and we just need to realize it. So I’m sure some of her teaching on shame is going to come from that foundation.

Anne: That’s sounds exactly right from the interview I heard with her. Like so many, she puts her finger right on the problem, and then there’s no solution that will carry you over the threshold to eternal life. You almost compound the problem. Every time you try to solve it, you make it worse. The whole narrative of Scripture is intended to deal with human self-centeredness and pride and shame and idolatry, turning humans instead toward God and away from self. But this way of reading the Bible and thinking about the gospel turns us back inward, so we can’t get out of the pits we keep digging for ourselves.

Alisa: Here’s quote that says it even more clearly in Brown’s book The Gifts of Imperfection. She says, “True belonging doesn’t require you to change who you are—it requires you to be who you are.” That’s exactly what you’ve been saying about Jen Hatmaker’s teachings and others’.

Anne: You have to just accept yourself. First you have to find yourself, find your true identity, and then accept it. Those are the two works of the Christian to become saved. Which is not the gospel. That’s not what the Bible is about at all. The Bible will tell you who you are, and then tell you have to be saved from it.

Alisa: A lot of people ask me, when I talk about Progressive’s beliefs, they’ll say, “Well, why do they still call themselves Christians? Why do they still claim that title? Why do they still want to have a gospel? I think you’re really putting your finger on it. They like Jesus—or at least they like their subjective definition of who Jesus is.

They like having tradition behind them. They even like certain rituals. You’ll find a lot of Progressives who still do the eucharist and say the creeds and things like this. I think there’s a sociological connection and a sentimental connection to Jesus and Christianity. But ultimately when you’re denying the fundamental definition of something like Christianity—if you’re going to deny the core of that—you’ve got to fill that with something else. You’ve got to have a cause and a gospel.

I have found, really across the board and from what you describe about Jen Hatmaker as well, that the Progressive gospel is heavily works based. It’s not a grace based gospel—it’s a works based gospel. Sometimes they’ll word it like “bringing the kingdom of heaven to earth now,” and a lot of times that will look like doing activism for gay rights, or in some cases for women’s reproductive rights (which again is just code for abortion rights), or even environmentalism.

It will take those forms because you have to have a cause. You’re not going to exist in a vacuum. So if you deny the core of what the thing really is, you’ll have to make it into something else. I think what you’re describing lines up perfectly with what I read in Progressive literature and what I hear on Progressive podcast: that the cause becomes building a better here and now, and loving people better—however they define love. It sounds like she’s right in the core of what the Progressive movement is all about.

Anne: I would say that’s absolutely true. I think she was this even before she came out as pro-LGBT. I really think if people had read her more carefully, they would not have been surprised at all. She wasn’t articulating the gospel clearly before that announcement, and she didn’t talk about the work of Christ. It is very, very human-centered and works based.

But the law is recast, as you said, to be here and now. The law isn’t what was revealed by God as the way human beings were designed to be and to reveal His character. The law is focused on caring for this earth and on being kind to each other. So there isn’t any eschaton, or rather, the eschaton is now. There isn’t any redemption—you have redeem your self by the power of your self acceptance.

It’s flat, and it’s difficult. As a Christian, I find it dull. I don’t understand why you would bother being in church. There are so many other more interesting religious systems.

Alisa: That is such a great point. If beauty was the source for truth and how we identify truth, or if perhaps good feelings was how we identified truth, there are other religious systems that have beautiful rituals that my fallen heart would resonate with.

Anne: I think if I wasn’t compelled by Jesus to be a Christian, I would go be Buddhist and live in Tibet and sit on a mountain. That sounds fun, and the food is great. I think that’s why Islam is such a compelling system, because it’s so clear and doable—it’s hard, but it’s doable. It has a certain kind of beauty to it. I don’t think the Progressive gospel is compelling or interesting. It’s hard, and it doesn’t take you outside of yourself at all. It doesn’t give you a break from your own psyche. I don’t really get it at an emotional level, but I think habit and nostalgia are good reasons to keep on with the church once it doesn’t have anything left of substance.

Sheila Bair

7/4/2019 07:49:55 pm

Please don't publish this. I really appreciate the content, but I just have to say that the background noise (like someone doing dishes) was very distracting. God bless all that you're doing. Thank you!

Alisa Childers

7/4/2019 08:00:58 pm

Hi Sheila, I totally get where you're coming from. I did my best to minimize the background noise but thought it was worth publishing because of the message. I updated the podcast notes to let people know that Anne agreed to do this podcast while her six kids are home on summer break. She is amazing!

Thank you for being a voice of reason in a world enraptured by false teachers. It’s my prayer that their voices will be silenced, though the Bible says this will be rampant in the end times. It’s heartbreaking to watch the falling away from truth.

Have you ever tried to get Jennifer on your podcast to ask personally ask her these questions? I can't find anywhere on her site where she outlines her core beliefs. No statement of faith. I am amazed at the music groups and speakers who expect to be invited to churches to 'minister', but do not even offer a statement of faith of any kind in their sites. You do! There needs to be a comprehensive site (maybe there is one already) called WorldView where you can look up an author, musician, professor, who claims to be Christian that reveals his or her core doctrinal beliefs and stand on social issues. BTW: We dropped MOPS because the representative I spoke with couldn't guarantee they would not have Jennifer speak at future events. Perhaps they are going the way of Progressive Christianity as well? Appreciate what you are doing.

Nice posting….(and I can live with the dishes 🙂 )

Progressive Christianity main purpose is always to erode separation in favor of "unity".

The concept of unity when it comes to the progressive "Christian" is always the "no-holds-bar" approach. It is to take anyone and everyone regardless of who they are. It is the manipulation of the words of Jesus Christ to justify their actions that what they do is under his "authority".

Salvation is misconstrued…..it is always made to look like something that is "good", and has the stamp of approval by Jesus Christ. Regardless of the sin, regardless of the behavior, regardless of circumstance, regardless of personal identity…..

It comes down that progressive Christianity does not understand the Gospel. It is nothing more than a subversion and always points back to the "New Age/Occult" movement….

Kim

7/10/2019 11:35:36 pm

Hello Alisa and Anne,

Anne you referenced a youtube video where Richard Rohr Says "Jesus came to change the mind of humanity about God. There was not a blood sacrifice necessary." Could you tell me what video you heard that from?

Thank you

https://cac.org/love-not-atonement-2017-05-04/

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.