And if I don’t forgive? (Matthew 18:35)

Jesus gives a single-sentence explanation of his parable about the unforgiving servant:

Matthew 18:35 (my translation, compare NIV)

“And that’s how my heavenly Father will treat you [plural], unless you each release your brother or sister from your hearts.”

Now we know who’s who in this story, and how they relate:

- The king is God — my heavenly Father.

- The servants are you (plural) — the kingdom of the king.

- The Son of the sovereign (implied by my heavenly Father) teaches kingdom ethics.

- The Son counts the servants as family — brothers and sisters.

- Counting offences (verse 21) doesn’t count as forgiving from the heart.

Most unsettling is the way Jesus presents his Father. God is like a king who in anger handed him over to the torturers (verse 34), and that’s how my Heavenly Father will treat you. Disturbing?

The problem is our tendency to read personally instead of corporately. The NIV mishandles this verse, giving the impression that God will be angry at me and send me to the torturers if I misbehave. What Jesus actually said is that this is how God would treat his kingdom (you plural), unless each individual in the family forgives the others from their hearts.

So instead of picturing God playing whack-a-mole with each individual, consider how Jesus’ audience would have understood the way God manages his kingdom.

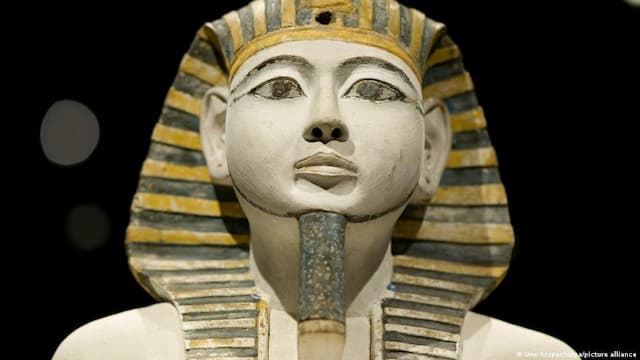

Old Testament kingdom context

Can you think of any Old Testament verses that provide background for the phrases Jesus used? Anything about God, in anger, handing his people over, to suffer at the hands of enemies?

Here’s a few:

Judges 2:14 (NIV) In his anger against Israel the Lord gave them into the hands of raiders who plundered them.

2 Kings 21:14–15 I will … give them into the hands of enemies. They will be looted and plundered by all their enemies; 15 they have done evil in my eyes and have aroused my anger from the day their ancestors came out of Egypt until this day.

Psalm 106:40–41 The Lord was angry with his people and abhorred his inheritance. He gave them into the hands of the nations, and their foes ruled over them.

Zechariah 11:6 “For I will no longer have pity on the people of the land,” declares the Lord. “I will give everyone into the hands of their neighbours and their king.”

Jeremiah 32:28–29 I am about to give this city into the hands of the Babylonians and to Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon, who will capture it. … They will burn it down, along with the houses where the people aroused my anger …

Ezekiel 21:31 I will pour out my wrath on you and breathe out my fiery anger against you; I will deliver you into the hands of brutal men, men skilled in destruction.

The Greek translation of these verses (LXX) uses παραδίδωμι as the verb to give them over, and Matthew uses the same verb in 18:34. There can be no doubt that Jesus was tapping into the familiar theme of the fallen kingdom that had expired God’s patience and was handed over to the nations where they were mistreated instead of enjoying God’s reign.

Jesus’ audience was living in this story. Restore us to yourself, Lord, that we may return; renew our days as of old unless you have utterly rejected us and are angry with us beyond measure (Lamentations 5:21–22).

Matthew’s kingdom context

This tragic kingdom story was the setting for Matthew’s good news — a phrase drawn from Isaiah 40. It doesn’t end with the family in exile (Isaiah 39:7). God would end the exile, (40:1-2), call them back from captivity (40:3-8), proclaim the good news of his reign with his people again (40:9-11).

Matthew says this is happening in Jesus the anointed son of David (1:1), born into the captivity (1:17), saving his people from their disobedience (1:21), restoring the presence of God with them (1:23). A voice in the wilderness was calling them back (3:3). The Son had been sent to them (3:17), the Spirit-led Son who overcame their enemy (4:1-11), restoring light where the kingdom first went dark (4:12-16), proclaiming heaven’s reign (4:17), enacted the good news of the kingdom (4:23).

So, had God’s people learned their lesson in the extended captivity? Were they ready to receive his Son, the servant of the Lord? Jesus knew: the son of man is about to be handed over into the hands of men (17:22).

This generation was no better. They would not give him the honour they owed him, (23:34-39). The city would fall again, suffering the torment of being crushed by their enemies again (24:1-28). They were still mistreating each other, calling for blood. It would be disastrous. This kingdom perspective makes perfect sense of what Jesus was referring to in 18:34-35.

Our kingdom context

So, does Jesus’ story have an application for Christians today? Absolutely. Just make sure you recognize the corporate nature of the application.

Those who acknowledge Christ as Lord live under his kingship, as citizens of the kingdom of heaven that is present in his reign. There’s no such thing as a private grievance between you and someone else. It’s a kingdom matter, because the other person belongs under Christ’s kingship.

Whenever I value someone’s debt as more than the person, I am no longer expressing the ethics of the kingdom. I am saying to God, “This is what you should do with your kingdom: in your anger, hand the evil-doer over to be tormented until they learn their lesson.” My actions are undermining the very basis on which God restores his reign to the earth — not giving people what we deserve. Forgiveness is the opposite of demanding repayment.

Each time one of us refuses to forgive, we are undermining the kingdom of Christ, interfering with the restoration God is bringing to the earth, reinforcing a message of demanding restitution.

I do understand that forgiveness isn’t easy. Pastorally, there can be many steps to processing forgiveness. What do you do if the other person doesn’t own their wrongdoing, doesn’t want to reconcile, or keeps perpetrating the harm? There are issues of truth, trust, and tyranny. We are not responsible for the other person’s actions. It can take time to align our desire’s with God’s so we can forgive from the heart (Romans 12:18-21).

But it does matter. Why?

- Forgiveness is the heart of kingdom ethics. Unforgiveness retains the oppression.

- Forgiveness is a king who gives his life to redeem (buy back) his people. Unforgiveness isolates us from this king.

- Forgiveness maintains community in Christ. Unforgiveness stops us being the good news community.

Conclusion

Shakespeare had it right in Romeo and Juliet. Unforgiveness destroys life for the next generation.

I don’t live in fear that God might torture me if I don’t forgive. I choose to forgive because our absurdly generous king was right after all, because unforgiveness undermines the community where Christ is present in the world, because the gospelling community has no credible message if we’re not embodying the reality of his forgiveness in our relationships with each other.

Unforgiveness is too expensive. Regardless of the size of the debt.

What others are saying

Peterson, Eugene, Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2005), 316:

Sin is basically a depersonalizing word or act. It is not, in essence, breaking a rule, but breaking a relationship. … Sin is a refused relationship with God that spills over into a wrong relationship with others … Love is the relational act par excellence just as sin is the de-relational act par excellence.

Michael F. Bird, Evangelical Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2013), 706–707

Newbigin wondered how it would be possible that the gospel should become credible in a pluralistic society and that people would come to believe that the power of God over human affairs was manifested by a man killed on a cross. For Newbigin the answer, the “only hermeneutic of the gospel,” is “a congregation of men and women who believe and live by it.” Jesus did not write a book, but he formed a community around him — a community that, at its heart, remembers and rehearses his deeds and words. …

We are the community of the gospelized: the company of the gospel, the public face of the gospel, the hermeneutic of the gospel. The worship, mission, ethics, symbols, testimony, and spirituality of the church are shaped by what it thinks of and what it does with the gospel of Jesus Christ. The gospel is the mark and mission of the authentic church of Christ.

Related posts

- When forgiveness outweighs repayment (Mt 18:23–35)

- Forgiveness: reciprocated or rescinded (Mt 18:23-35)

- How far does forgiveness go? (Mt 18:21-22)

- How serving can ransom many (Mt 20:28)

Seeking to understand Jesus in the terms he chose to describe himself: son of man (his identity), and kingdom of God (his mission). Riverview Church, Perth, Western Australia

View all posts by Allen Browne