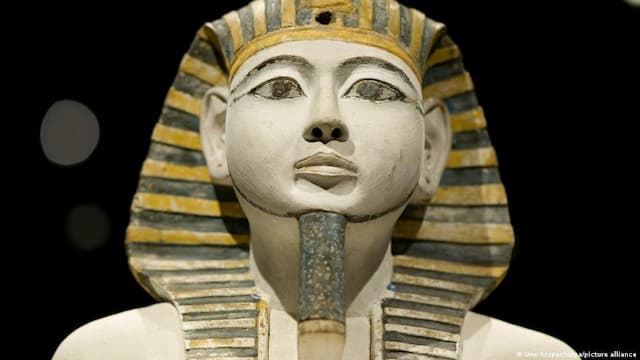

Joseph’s love story (Genesis 41:44-52)

Did you know that Joseph married an Egyptian?

Genesis 41 (NIV)

45 Pharaoh gave Joseph the name Zaphenath-Paneah and gave him Asenath daughter of Potiphera, priest of On, to be his wife. …

50 Before the years of famine came, two sons were born to Joseph by Asenath daughter of Potiphera, priest of On.

Joseph is an amazing character. Despite being catapulted to power from prison, Joseph is one of the few not corrupted by power. But his lifestyle choices in exile still present problems for observant Jews.

Asenath is not just a foreigner; she’s an idol-worshipper. Her hometown was On, also known as Heliopolis — “city of the sun,” in honour of sun-God Re. Her father was a priest of Re, and his name (Potiphera) means “he whom Re has given.” The priest of Re devoted his daughter to the Egyptian goddess Neith, for Asenath means “belonging to Neith.”

Just as Francine Rivers writes historical fiction today, a writer from around Jesus’ time wrote a novella to clarify Joseph’s values:

How could Joseph — the model of chastity, piety, and statesmanship — marry a foreign Hamitic girl, daughter of an idolatrous priest? Jewish theology and lore found many answers to this intriguing question and expanded some into narratives. Joseph and Aseneth, the longest of these stories, is a full-fledged romance by an anonymous author; it is nearly twice as long as Esther, and a little longer than the Gospel of Mark.

— C. Burchard, “Joseph and Aseneth” in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), 2:177

Joseph and Aseneth is quite the creative romance. Asenath is presented as a strong woman, refusing her father’s arrangements for her to marry Joseph, only to fall for him when she finally meets him. But Joseph rejects her, insisting he cannot kiss lips that kiss idols and eat at their table. Eventually Asenath recants her idols, Joseph accepts her repentance, they get together and live happily ever after.

That’s the sanitized version, rewriting history so Joseph isn’t setting a bad example. As the leading son of Jacob’s family and father of two tribes, it’s embarrassing when he doesn’t comply with the patriarchs’ strong reactions against mixing godless foreign blood into the Abrahamic family (Genesis 24:3; 28:6, 8; 38:2).

The more difficult story

The truth is more brutal than the fiction. Truth is, neither Joseph nor Asenath had any choice in this politically arranged marriage.

Pharoah never asked Joseph if he wanted a different identity with a new name, if he wanted an Egyptian wife, if he wanted to travel all over Egypt enforcing Pharaoh’s decrees, or if he wanted to spend the rest of his life serving Pharoah rather than the God of Abraham:

Genesis 41:45–46 (NIV)

45 Pharaoh gave Joseph the name Zaphenath-Paneah and gave him Asenath daughter of Potiphera, priest of On, to be his wife. And Joseph went throughout the land of Egypt.

46 Joseph was thirty years old when he entered the service of Pharaoh king of Egypt. And Joseph went out from Pharaoh’s presence and travelled throughout Egypt.

That’s how Genesis explains Joseph’s marriage. There’s no need to explain Pharoah as king of Egypt, unless you want to draw attention to the matter of power.

Starting with the Garden, Genesis tells the story of a world that does not recognize God’s authority. Starting with Abraham, Genesis describes God raising up a nation under his reign so the nations see what they’re missing. During this long-term restoration project, the heavenly sovereign is astoundingly gracious with this present evil age. Joseph has been sold out by his brothers, so he’s not free to serve God in the land promised to Abraham.

So, rather than idealize Joseph’s marriage with romantic imagination, it might be better to view it as an example of God’s astounding grace in a world gone wrong, a world where those in power force their authority on us all.

And God is still able to form two leading tribes of Israel out of this mess:

Genesis 41:51–52 (NIV)

51 Joseph named his firstborn Manasseh and said, “It is because God has made me forget all my trouble and all my father’s household.” 52 The second son he named Ephraim and said, “It is because God has made me fruitful in the land of my suffering.”

Making sense of life

It’s hard to make sense of life when you’re not in control. Joseph was sold into slavery by his brothers. He was thrown into prison by false allegations. He still can’t go home; he’s forced to serve Pharaoh.

Not hard to see why Joseph calls his first son, Forget (Manasseh).

And his second son is Fruitful-Again (Ephraim). In Genesis, life is productive because God blessed the earth and its creatures with fruitfulness (1:11, 22, 28; 9:1; 28:3). While he’d like to forget the oppressive years, Joseph’s life is fruitful again.

That message reverberates through Scripture. While we experience thorns and thistles and deserts and oppression, God decreed the world to be fruitful in the beginning, and what he decreed will come to pass in the end.

The word of the Lord does not return empty like an ineffective echo. It achieves what God decreed: fruitfulness in place of suffering, productive trees instead of thorns (Isaiah 55:11-13).

That’s Joseph’s testimony. He doesn’t credit Pharoah or his cupbearer with his restoration. Joseph’s destiny was never in their hands or his own control. God has made me forget all my trouble … God has made me fruitful in the land of my suffering.

The gospel of the kingdom of God assures us that God will complete what he has begun. We can forget what came before and lean into the astounding global reconstruction God is completing in Christ.

Here’s what counts:

Philippians 3:13–14 (my translation)

Just one thing: forgetting what was before, stretching forward to what’s ahead, 14 I pursue the goal — the prize of the higher call of God [to participation] in Messiah Jesus.

Related posts

- Rebekah’s romance (Gen 24:22-67)

- The divine romance (Ep 5:31-32)

- Zechariah’s vision of God’s reign (Zech 14:4-21)

- The destiny God has planned for us (Eph 1:4-10)

- Finding God in an unjust world (Gen 39)

Seeking to understand Jesus in the terms he chose to describe himself: son of man (his identity), and kingdom of God (his mission). Riverview Church, Perth, Western Australia

View all posts by Allen Browne