Happy Thanksgiving: A Republic If You Can Keep It. - Lin Wilder

Happy Thanksgiving: A Republic if you can keep it.

It was exactly 400 years ago, in November of 1621, that something happened-some type of meal took place- between the English settlers and the Massasoit and others of the Wampanoag settlement of native Americans. The details of that shared meal in what would become Plymouth Massachusetts are fodder for contention and a variety of opinion. That fact has done little to unravel this uniquely American idea of annually giving thanks to our sovereign God-one that has persisted for four centuries.

The pivotol role of the Indian Squanto or Tisquantum, in the survival of the Englishmen that first year is well-known. But the tale of his kidnapping as a boy in 1608 by English traders and subsequent return years later on another English ship can only be thought of as miraculous.

“One day in the spring of 1621 a local native walked out of the woods to greet them. Somehow he actually spoke perfect English; and as it happened, he had grown up on the very land where they had settled. Because of this, he knew everything there was to know about how to survive there. He knew and showed them the best way to plant corn and squash so that they would thrive in that environment. He knew and showed them how to find fish and lobsters and eels there. He knew and showed them much that they couldn’t have known themselves. And because his tribe had perished, he had little better to do than help these suffering strangers. So the Pilgrims adopted him. And Squanto helped them immeasurably, likely saving their lives and almost certainly making it possible for them to continue there on this foreign soil. Could this all have been happenstance?“

For all the reasons dividing this country 400 years later, in November of 2021, whether because of the color of our skin, type of religion or lack of it, differing opinions among us believers, or our politics, President Abraham Lincoln’s decision to proclaim the last Thursday of November as a national day of thankfulness in October of 1863 compels us to stop.

In our tracks.

And slowly, carefully ponder the man’s words, written amidst incalculable, incomprehensible suffering of the man-this American President, and his American citizenry, battling for the soul of the nation. In the midst of all the horror, President Lincoln chooses to institutionalize this American tradition of giving thanks for all things.

Lincoln’s Proclamation is copied and pasted at the end of this piece

but first we must consider that intriguing phrase, “A republic if you can keep it.”

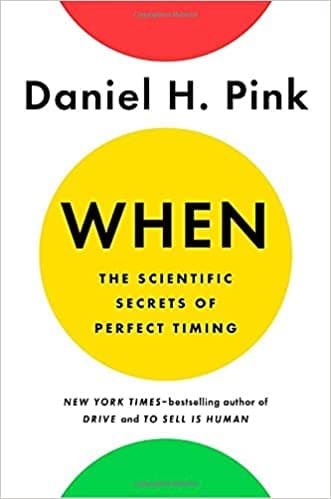

If you’ve been reading my articles for a while, you might recall that I’m a fan of Eric Metaxas, author of Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Spy, Prophet.

That phrase, “a republic if you can keep it,” derives from an alleged conversation between Benjamin Franklin and a woman passing by as Franklin left the building housing the Constitutional Convention.

In his book of the same name, Metaxes writes,

In the summer of 1787, Benjamin Franklin was leaving the Constitutional Convention when a Philadelphia matron named Mrs. Powell asked him a question. “What have you given us, Dr. Franklin,” she asked. “A monarchy or a republic?”

Did she really think a monarchy was still possible?

From where we sit today, it’s easy to dismiss the question as silly. After all, who can imagine a monarchy in America? But we have to remember that in 1787 no nation had ever managed — or dared — to attempt genuine self-government. It was a rather wild experiment, and it hadn’t been going so well, which is why the Founders had to gather again at Independence Hall eleven years after declaring independence. So the question was a real one. What had the Founders discovered in trying to come up with a new Constitution? Was a genuine republic simply not possible?

Franklin’s response to Mrs. Powell’s question has become famous. “A republic, Madam,” he said. “If you can keep it.”

234 years later, we must wonder if, indeed, we can keep it.

Metaxes, like the former Secretary of State, Anthony Barr, believes we can keep our republic only if we retain our grip on religious freedom as axiomatic to America. Metaxes’ book, If You Can Keep It, reviews the ingredients which went into this untried experiment unseen in human history: a people being given the right to govern themselves.

Metaxes is a gifted writer. Hence, he knows that understanding is impossible without context and therefore reviews briefly the history of nations before the “American experiment.” Emphasizing how stunningly implausible was the American notion of self-governance in the mid-eighthteenth century because to us it’s become common place. It is so very useful to consider the facts of a thing, draw back so that we can see more clearly. Metaxes helps us do this.

Many claim that our nation has never been so divided.

That the chasms beween different groups of Americans are historically vast.

And yet, a mere glance at our 234 year history reveals that the divisions among and between Americans are rarely absent. And are frequently so wide as to be on the brink of war. The new nation nearly dissolved eleven years after it was formed. The attacks by 400 desperate Massachusetts farmers on courthouses and federal property known as Shays Rebellion required federal milita to end it. The rebellion demonstarted the need for a government that was stronger than the 1776 Articles of Confederation.

But not too strong.

Metaxes writes of these founders. Adams, Jefferson, and Bejjamin Franklin, a man known for his lack of interest in religious orthodoxy, stated publically the essential ingredient of a self-governing people: religion.

Only a virtuous people are capable of freedom.

Benjamin Franklin

What do we mean by freedom of religion?

By faith?

By virtue?

By freedom itself?

Quoting his friend Os Guiness, Metaxes writes that

“….when reduced to its most basic form, that freedom requires virtue; virtue requires faith; and faith requires freedom. The three go round and round, supporting one another ad infinitum. If any one of the three legs of the triangle is removed, the whole structure ceases to exist.”

The book is filled with interesting, even surprising facts. But the section on George Whitefield, the “spiritual father of the United States” and subsequent catalyst for the “The Great Awakening” is especially fascinating.

“The most august dukes and earls were sinners who could be saved only by grace, the very same grace that saved the commonest commoner. The Gospel of Christ was the most powerful sociological leveler in history, and although the message had existed for seventeen centuries, it would burst into full bloom only now—at this crucial point in history—under the watering can of Whitefield’s preaching. And over the decades this changed the colonies and created an American people. The egalitarian strains of the Gospel extended to women and blacks as well. Many female preachers were spawned by the revival of the Great Awakening and many African American preachers too. Unlike most of the mainline ministers of his day, Whitefield often spoke to “Negroes” and once remarked that he was especially touched when one of them came to faith. One of them even asked Whitefield, “Have I a soul?” That Whitefield believed he did meant that the Negro was in this most important respect perfectly equal to whites. Whitefield’s preaching was a great social leveler throughout the colonies. But it was a great uniter of the people in the colonies too. By the time Whitefield died in 1770, an inconceivable 80 percent of the population of the American colonies had heard him preach at least once. By traveling as he did, he accomplished what no one else had ever done. He became known to all in the colonies equally. He was the first American celebrity, but he was much more than a mere celebrity.

If You Can Keep It

Ths is a book filled with tales of American heroes and

unabashed in the critcal need to find and celebrate honor, goodness, self-denial: the real American dream of sacrifice and nobility. For a freedom so precious, so all-consuming that we’ll give Him our lives. His writing is replete with the founders knowledge that we are but men.

Metaxes’ writing of another “miracle,” the Constitution is riveting:

“But toward the end of the convention, after endless battles and little progress, things looked hopeless. The disagreements and arguments had mounted to an impossible height, so the eldest delegate, Benjamin Franklin, gave a speech to the assembly, imploring them to turn to God to break the impasse. Franklin and Jefferson were the least overtly religious of the founders, so the idea that Franklin should be the one to beseech the assembly to turn to God in prayer for an answer to their problems is evidence of their desperation, and it is startling…

As we know, in the end all impasses were broken, compromises on all issues struck, and solutions found. There was what all felt to be a truly remarkable—almost odd—willingness for each side to set aside its concerns for the good of the whole. The spirit of selflessness and compromise that came over this body of opinionated, brilliant, and principled men was in the end sufficient for them to ratify the great document called the Constitution.”

Near the end of his book, Metaxes asks how Americans could have gone from admiration and reverence for our hard-fought traditions and ideals to ….this – in just a few decades. Suggesting the answer, the author reveals that eerie prescience which would characterize Abraham Lincoln’s ( “the greatest president’s”) presidency.

When just twenty-eight years old, Lincoln addresses the Springfield Young Men’s Lyceum. In speaking about the “salubrious” situation with which Americans find themselves in 1837 he asks rhetorically what could be the source of the undoing of this great country?

Shall we expect some transatlantic military giant to step the ocean and crush us at a blow? Never! All the armies of Europe, Asia, and Africa combined, with all the treasure of the earth (our own excepted) in their military chest, with a Bonaparte for a commander, could not by force take a drink from the Ohio or make a track on the Blue Ridge in a trial of a thousand years. At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer. If it ever reach us it must spring up amongst us; it cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen we must live through all time or die by suicide.

Here is the text of Abraham Lincoln’s proclamation of the last Thursday of each November a national day of thanksgiving.

The year that is drawing toward its close has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and

healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the

source from which they come, others have been added, which are of so extraordinary a nature

that they cannot fail to penetrate and even soften the heart which is habitually insensible to the

ever-watchful providence of Almighty God.

In the midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity, which has sometimes seemed to

foreign states to invite and provoke their aggressions, peace has been preserved with all nations,

order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed

everywhere, except in the theater of military conflict; while that theater has been greatly

contracted by the advancing armies and navies of the Union.

Needful diversions of wealth and of strength from the fields of peaceful industry to the national

defense have not arrested the plow, the shuttle, or the ship; the ax has enlarged the borders of our

settlements, and the mines, as well of iron and coal as of the precious metals, have yielded even

more abundantly than heretofore. Population has steadily increased, notwithstanding the waste

that has been made in the camp, the siege, and the battlefield, and the country, rejoicing in the

consciousness of augmented strength and vigor, is permitted to expect continuance of years with

large increase of freedom.

No human counsel hath devised, nor hath any mortal hand worked out these great things. They

are the gracious gifts of the Most High God, who while dealing with us in anger for our sins,

hath nevertheless remembered mercy.

It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently, and gratefully

acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American people. I do, therefore,

invite my fellow-citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and

those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of

November next as a Day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in

the heavens. And I recommend to them that, while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him

for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national

perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows,

orphans, mourners, or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably

engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty hand to heal the wounds of the

nation, and to restore it, as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes, to the full

enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility, and union.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United Stated

States to be affixed.

Done at the city of Washington, this third day of October, in the year of our Lord one thousand

eight hundred and sixty-three, and of the Independence of the United States the eighty-eighth.

“The great writer G. K. Chesterton once said that “America is the only nation that is founded on a creed.” We have touched upon this in a previous chapter, but it is worth underscoring. How can it be that with roughly two hundred countries in the world today, America is still the only one that can be described that way? And yet it is. And the creed upon which it is founded is not a parochial creed but a universal one, declaring that all men are created equal and that government exists only by the consent of the governed. As President Truman put it, “Being an American is more than a matter of where you or your parents came from. It is a belief that all men are created free and equal.”

Metaxas, Eric. If You Can Keep It (p. 184). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.