Kingdom work: the last 150 years

If I made the kingdom of God the centre of my thought and activity as Jesus did, where does it lead me? As I began this journey seven years ago, I wondered out loud, “Would seeking the kingdom make me an activist?”

For some, the gospel is personal salvation (John 3:16). For others, the gospel calls for action: caring for the poor, seeking justice the powerless, protecting the environment. What does Jesus’ gospel — the gospel of the kingdom — call us to say or do?

Leo Tolstoy is best known for War and Peace. In the decades before the Russian revolution, Tolstoy called people to take a different path, to pursue non-violent resistance as the path to the kingdom of God:

That is why that Power cannot require of us what is irrational and impossible: the organization of our temporary external life, the life of society or of the state. That Power demands of us only what is reasonable, certain, and possible: to serve the kingdom of God, that is, to contribute to the establishment of the greatest possible union between all living beings — a union possible only in the truth; and to recognize and to profess the revealed truth, which is always in our power.

“But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness, and all these things shall be added unto you.” (Matt. vi. 33.)

The sole meaning of life is to serve humanity by contributing to the establishment of the kingdom of God, which can only be done by the recognition and profession of the truth by every man.

“The kingdom of God cometh not with outward show; neither shall they say, Lo here! or, Lo there! for behold, the kingdom of God is within you.” (Luke xvii. 20, 21.)

— Leo Tolstoy, The Kingdom of God Is Within You, 254–265.

Russia rejected Tolstoy’s plea for peaceful grassroots transformation, overturning the Czars in one of the most violent revolutions ever. But Tolstoy’s voice was not lost: among those he influenced were Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King.

On both sides of World War I, people saw fighting for their government as their duty. Other voices called Christians to represent God’s kingdom instead. It was during the Great War that Walter Rauschenbusch penned these words:

The social gospel … plainly concentrates religious interest on the great ethical problems of social life. … The non-ethical practices and beliefs in historical Christianity nearly all centre on the winning of heaven and immortality. On the other hand, the Kingdom of God can be established by nothing except righteous life and action.

— Walter Rauschenbusch, A Theology for the Social Gospel (New York: Macmillan, 1917), 15.

Parts of the church were horrified by this “social gospel.” For them, preaching the gospel meant ensuring people went to heaven when they died. In 1922, evangelist R. A. Torrey warned the church that the social gospel was a false gospel, a form of works-righteousness:

Many men say that the way to get into the Kingdom of God is by leading an upright life, … practising “the social gospel” … Turn to John 3:3, 5 and you will see exactly what God says. “Jesus answered and said unto him, Verily, verily, I say unto thee, Except a man be born again, he cannot see the Kingdom of God.” … God says that the only way to enter the Kingdom and be saved is by being born again …

— Reuben Archer Torrey, The Gospel for Today (New York; Chicago: Fleming H. Revell, 1922), 212–213.

The one thing that mattered for Torrey was this: “What must I do in the life that now is that I may have a satisfactory and glorious eternity?” (ibid, 146, emphasis original).

In the 1960s, those who followed Moody’s and Torrey’s other-worldly gospel were horrified to see a Baptist pastor calling the church to confront the deeply ingrained racial justice of this world. “I have a dream …” cried Martin Luther King Jr. His dream saw the kingdom of God transforming this world so that blacks and whites could live together.

Eventually the church realized it was a false dichotomy to argue over whether the gospel was good news for this world or the next. Billy Graham and John Stott were among the leaders who set up The First International Congress on World Evangelization in 1974. The Lausanne conference recognized the church’s mission as “holistic … both evangelism and social justice.”

But how do we do this? Where do we place the emphasis? What does it look like to announce the gospel of the kingdom? Should the church engage in non-violent resistance as King had done? Should we go further?

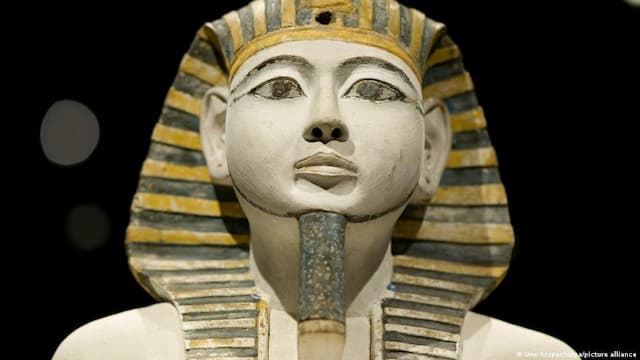

Catholic missionaries in South America felt they could not sit on the sidelines and watch their flock under systemic oppression. The God who liberated Israel from Pharaoh is still liberating people from slavery today. Gustavo Gutierrez labelled it kingdom work:

The Kingdom of God necessarily implies the reestablishment of justice in this world, then we must believe that Christ says the poor are blessed because the Kingdom of God has begun: “The time has come; the Kingdom of God is upon you” (Mark 1:15). In other words, the elimination of the exploitation and poverty that prevent the poor from being fully human has begun; a Kingdom of justice which goes even beyond what they could have hoped for has begun. They are blessed because the coming of the Kingdom will put an end to their poverty by creating a world of fellowship.

— Gustavo Gutierrez, A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics, and Salvation (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1988), 170–171.

Some proponents of this liberation theology went as far as taking up weapons to fight against the oppressive regimes and liberate their people. The Catholic hierarchy applauded their concern for the poor, but rejected violence as the path to peace.

So, how can the kingdom of God be restored in a violent world where powerful people rule through armed force? How can Jesus’ action, more than 2000 years ago, sort out injustice today? Why is it taking so long?

What should followers of Jesus be doing to announce and enact the good news of the kingdom of God? As difficult as these questions are, they may be the most important questions the church can ask.

Seeking to understand Jesus in the terms he chose to describe himself: son of man (his identity), and kingdom of God (his mission). Riverview College Dean

View all posts by Allen Browne