Questions take you deeper (Ephesians 2)

Here’s an example of how asking good questions leads to a richer appreciation of what God is doing.

When you read Scripture, what are you looking for? It’s not enough to approach the Bible like a shopping trip, to pick up some things that appeal to you. The Bible changes us. It’s the revelation of the God who is reshaping us into community in his image.

Questions help open us to that transformation, beyond the way we currently think and live. Rich communal understanding and life grows from asking good questions together.

An example from a recent post. Ephesians 2:1 (NIV) says, As for you, you were dead in your transgressions and sins. We asked, “Who is the you?” The tendency is to assume it’s me, because our culture is individualistic. But you is plural, so perhaps it’s us? But two verses later, the writer switches from you to us. Turns out he’s using we to mean his own people (fellow Jews), and addressing people of other nations (gentiles) as you.

That leads to another question. What were the transgressions and sins of the gentiles? The sins of the Jewish nation could be any violations of the law God gave them at Sinai, but how were gentiles disobedient to God?

From a Jewish perspective, there are some indications that the sins of the nations are primarily acts of violence. It was violence that corrupted humanity even before Abraham (Genesis 6:11). So God issued an anti-violence command to everyone, in the context of God’s covenant commitment to never give up ruling us all, no matter how hard we are to manage (Genesis 9:4-17). Kingdoms are built through war: we’re introduced to that idea at the heart of the chapter on the nations (Genesis 10:8-12).

In Ephesians 2:1, the parallel word for sins is transgressions. Transgressing means overstepping a boundary. In Hebrew thought, everything, including the existence of the nations, is decreed by God: “The Most High gave the nations their inheritance, when he divided all mankind, he set up boundaries for the peoples” (Deuteronomy 32:8). But since the nations do not recognize the authority of the one who gave them their lands, they conduct wars to gain more — transgressing the boundaries he set.

Most significantly, the nations’ transgressions include their failure to honour the boundaries God set for Jacob’s descendants (Deuteronomy 32:9). Israel lost the Promised Land when Assyria took the north and Babylon took what left (2 Kings 17, 25). The sins of the nations are clear: they transgressed the boundaries set by God, decimating the entire Abraham project.

As an exile in Babylon, Ezekiel was distraught that there was nothing left. “The end! The end has come,” he grieved (Ezekiel 8:2). What had been the Holy Land was defiled with the bones of dead soldiers, slaughtered by the sins of the nations (Assyria and Babylon). With no one to bury them, the dead bones lay in the open, bleached by the sun, visible symbols of the death of God’s nation.

But the Sovereign Lord — the eternal sovereign who rules the whole earth, even after the Davidic kingship had ceased representing him — had a message for his human servant. Even though the transgressions and sins of the nations had destroyed Israel, God would yet breathe life into the dead bones. The whole dead corporate entity would rise again (Ezekiel 37:9-14). Miraculously, this applied to both houses of Israel: the Joseph tribes destroyed by Assyria’s transgression in 722 BC, and Judah destroyed by Babylon’s transgression in 587. This resurrection would reunite the kingdom that divided when Solomon died (1 Kings 12). God would raise up a single nation from two parts (Ezekiel 37:15-23), with one Davidic king to lead them (37:24-25), as a covenant of peace (37:26), with a restored temple/dwelling of God (37:27), so the nations know the Lord (37:28).

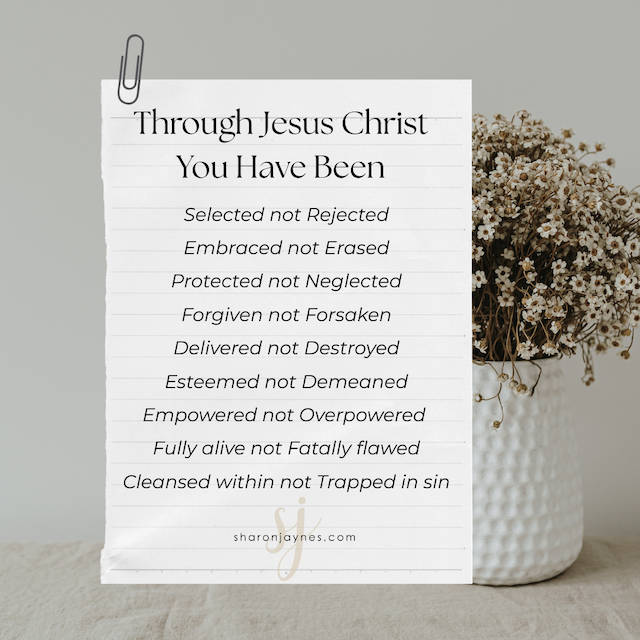

Did you recognize it? Ephesians 2 unfolds exactly along the lines of Ezekiel 37. It starts with the transgressions and sins of the nations, and the associated death of the covenant people (Ephesians 2:3). But God resurrected his covenant people in his anointed, in the resurrection of the Davidic Messiah (2:4-7). Miraculously, God even resurrected the dead nations in the Messiah, even though their efforts had contributed nothing useful at all (2:11-13). So God did much more than reconcile the two houses of Israel: he established a peace covenant with everyone — Jews and gentiles, the warring divisions of humanity. God is building both groups into a single new restored humanity, in the Messiah who is the chief cornerstone of the whole project, the temple where God lives among humans (2:19-22).

In summary, Ephesians 2 explains how the valley-of-dry-bones-prophecy is fulfilled in the Messiah. For further detail, see “The Use of Ezekiel 37 in Ephesians 2” in Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 50:4 (2007): 714–733.

So how did we get to this insight into Ephesians 2? It started with a question — a question that moved us beyond what the text might mean for “me,” a question that led us into the astounding message called the gospel of peace — the good news of Jesus reconciling all the peoples of the earth to God and to each other, in himself.

Ask questions that go beyond me, to who God is and what he is doing.

Related posts

- In Christ: humanity restored (Eph. 2:1–10)

- Good news of peace (Eph. 2:11-22)

- The destiny God has planned for us (Eph. 1:4-10)

- Kingdom or Church? (Eph. 1:18-23)

Seeking to understand Jesus in the terms he chose to describe himself: son of man (his identity), and kingdom of God (his mission). Riverview College Dean

View all posts by Allen Browne