The binding of Isaac (Genesis 22:3-9)

In the story of the binding of Isaac, is there a hint of the suffering God’s people would endure in the years ahead?

There are times when life is good, when you feel you have God’s provision, his blessing. There are also times when you don’t receive what you prayed for, or you lose what’s most precious to you. It’s in the difficult moment that you discover the basis of your faith. Do you love God for the benefits he gives? Or do you love God for who he is, holding onto him even when you lose everything else?

That’s the test Abraham faces in Genesis 22. After all these years, he finally has the son through who God will build a nation and restore the blessing of his reign over all nations. But is Abraham following God for the blessings, or for God himself? What if Isaac was taken from him? What if he had to lay Isaac down?

It’s the most difficult journey of Abraham’s life. Isaac joins him, though he does not know what’s happening or why. They travel to “the land of Moriah.” We don’t know any region by that name, but after the Jews returned from exile, they referred to the temple mount (Zion) as Mount Moriah (2 Chronicles 3:1). If it is the same place, I wonder how much God told Abraham when he referred to “one of the mountains of which I shall tell you” (22:2).

Isaac questions whether they have something to sacrifice. His father assures him that God will see to the matter of the lamb (22:7-8). For three days, Abraham has felt the death of this son. They scale the mountain. Abraham builds the altar, and binds Isaac to it.

The narrator tells the story from Abraham’s point of view, but its Jewish hearers identify with Isaac. At this point, the whole Jewish nation was still “in Isaac.” Their entire future depended on what happened to Isaac. Why would Abraham bind them to an altar of sacrifice? Given the sufferings they have faced over four millennia, you can appreciate their enigmatic question. Their ancestor Abraham bound them to the altar without explanation, in the hope that somehow, through their sufferings, God would restore his creation. Even if they don’t understand it, their task is to walk with Abraham, as Isaac did: “So they went both of them together” (22:6, repeated in 22:8).

The binding of Isaac feels like the experience of the Jewish people. When God finally saw fit, Isaac was released. And that remains the Jewish hope: that one day, when God sees fit, they will be released from the altar of suffering that they have endured so long.

Christian readers need to appreciate this Jewish perspective. I believe they’re right: the sufferings of God’s people are not meaningless. Those sufferings can somehow be redemptive. Have you noticed how many Davidic psalms are laments? Just as Isaac was bound in the hope of being released, King David experienced and embodied the sufferings of God’s people. When it seemed that God had forsaken his people, their king carried their sufferings for them, crying out, “My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?” (Psalm 22:1). The prophet Isaiah described Israel as God’s suffering servant, assuring them their sufferings were not meaningless. Through their sufferings, Israel’s God would ultimately bring healing and restoration not only to them but to his world (Isaiah 40 – 66).

This great redemption was to come through an anointed son of David. Would it be surprising if this Messiah, like Isaac, like Israel, embodied the sufferings of God’s people? A suffering son of David who would release his people, a son of Abraham who was bound in order to release God’s people—are there hints of such a great reversal in the Law and the Prophets?

Would it be so strange for the kingdom of God to be restored not by a Messiah who slaughtered his enemies, but by a son of David who embodied the sufferings of his people to bring the nations back under God’s sovereign rule? Wouldn’t that be just like Israel’s amazing God—doing so much more than anyone imagined, entering into the suffering of his people?

What others are saying

Nahum M. Sarna, Genesis, JPS Torah Commentary (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1989), 153:

bound: The Hebrew stem ʿ-k-d is found nowhere else in the ritual vocabulary of the Bible. In postbiblical texts it is a technical term for the tying together of the forefoot and the hindfoot of an animal or of the two forefeet or two hindfeet.

K. A. Mathews, Genesis 11:27–50:26, New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2005), 285:

God’s integrity is not questioned for his trying of Israel, and the test of Abraham is on the same level, for it is a prototype of later Israel’s trials (Gen. Rab. 55.1–3). Christian tradition, however, focuses on the fulfillment of the promises (Heb 11:17–19; Jas 2:21–23) since Isaac alone could fulfill the promises, as God himself stated (21:12), making it certain that the boy would somehow survive.

Read Genesis 22:3-9.

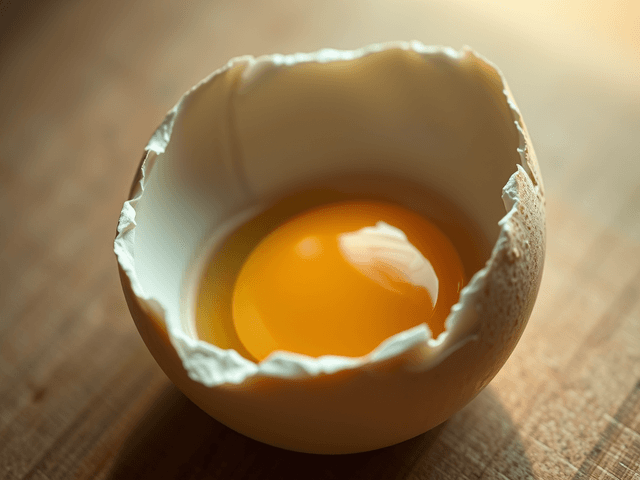

Mosaic from synagogue at Sepphoris (5th century AD)

Photo by Allen Browne, 2014

[previous]

[next]

Seeking to understand Jesus in the terms he chose to describe himself: son of man (his identity), and kingdom of God (his mission). Riverview College Dean

View all posts by Allen Browne